Dylanology 17 (September 2022): Bing and Bob and the Eternal Question of Plagiarism

The World Chess Champion stirred things up by accusing an opponent of cheating. On that note: is Dylan’s song “When the Deal Goes Down” plagiarism and thus cheating, or is the issue more complex?

In 2004, journalist David Gates interviewed Bob Dylan for Newsweek regarding his autobiography Chronicles. In a Live Talk session in connection with the interview, Gates was asked: “Did Bob share any details with you regarding the songs for his next album? What’s the scoop?”

Gates’s answer was surprising:

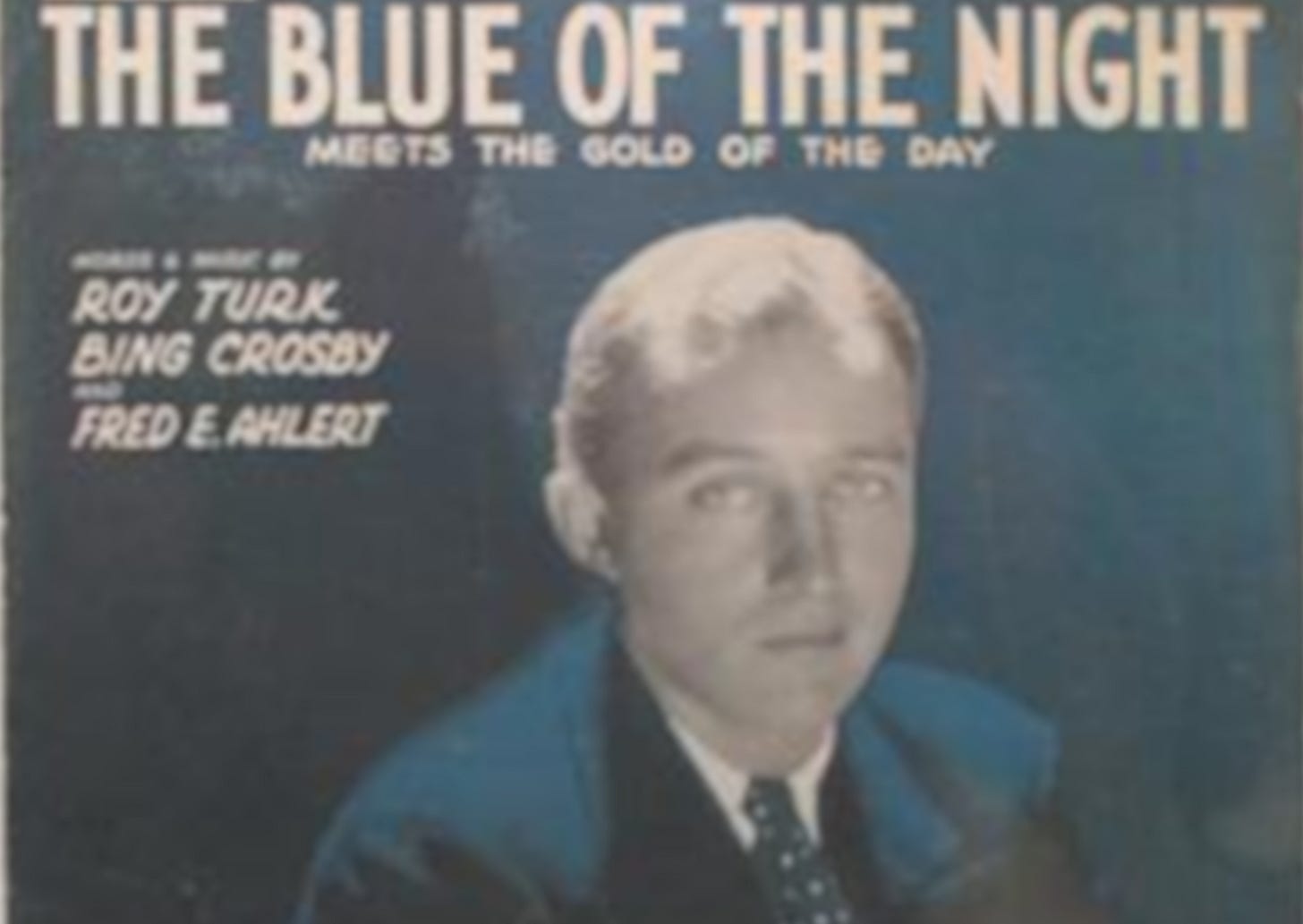

He did say he’s written a song based on the melody from a Bing Crosby song, Where the Blue of the Night Meets the Gold of the Day. How much it’ll actually sound like that is anybody’s guess. (Newsweek Live Talk, Sept. 2004.)

Two years later, Modern Times came out, and we didn’t have to guess anymore: yes, Dylan was indeed working on that Crosby song, and the result was When the Deal Goes Down.

On the face of it, there is no room for discussion: had Dylan acknowledged the loan and written “Words: Bob Dylan, music: Fred E. Ahlert”, then nobody would have had any problem with it. But when it says on his web page:

it becomes problematic.

One might say that that signature is a crystal clear example of plagiarism. And yet: Dylan has not tried to make a secret of the source of “inspiration” – not only has he discussed it with a journalist, but he has also chosen Bing Crosby’s signature tune. In Dylan’s mind, this is not something to be ashamed of or concerned about.

A common line of argument that is always brought up by those who want to defend Dylan from any suspicion of wrongdoing, is that this is the folk process; you pick something from the hallowed Pool of Song, you elaborate it, and put it back in the pool again, and everyone is a little bit happier and a little bit richer.

This line of argument tends to downplay the “richer” part – that Dylan is actually making good money and a name for himself from someone else’s creative work – as well as the huge difference between working on some anonymous folk song on one hand, and on an independent piece of music, not yet in the public domain and with a known composer, on the other.

I am critical of such an apologetic approach. In this particular case, however, I think it can be argued that the case of plagiarism is actually less clear-cut than it may seem, but the argument follows a different path.

But let’s first hear –

The Plagiarism Hunter’s Argument: Chords and Melodies

One thing is beyond discussion: the chord sequence is virtually identical in the two songs. Below are the two melodies. Bing’s version is on the top, Bob’s below:

An apologete might point out that although the intro is identical and the chords are the same, the melody line in the very first phrase (“When the blue of the night”/“In the still of the night”) is not the same – actually not a single tone coincides.

However, the melody at this point is quite generic in both versions; it consists of mostly stepwise motion filling in the outline of some of the main tones of the chords (f and a, followed by e and g, respectively):

And as soon as the melody becomes distinctive, harmonically or melodically, Dylan follows Bing Crosby to the note. The first phrase in both versions ends with exactly the same figure, landing on a d flat at “day/light” – a tone that is quite remote from the tone material of the key of the song, and a very un-Dylanly melody line, given that (intended) chromaticism is usually not a tool in his box:

And the first segment ends identically, with the equally distinctive melody at “someone waits for me” / “wisdom grows up in strife”:

This section of music is repeated, followed by a contrasting section, after which the initial section is repeated once again, so that the full form of the verse is AABA.

In the contrasting third line (B), every note in the melody appears in exactly the same sequence as in Crosby’s version. So again: evidently, Dylan has just stolen Bing’s song:

Or has he?

The Apologetic View

Have a look at Bing’s initial phrase again:

What is the most important musical contents here? The phrase is shaped so that the descending fourths a-e and g-db are emphasised (marked in red). Rhythmically, it’s a constant ti-ti-taaa, ti-ti-taaa (whenthe bluuuue – ofthe naaaaaight, sung Jiminy Cricket style), where the constant wave-like motion of the melody gives it a certain nightly calm.

Compare this to Dylan’s different renditions of the first phrase (only the first two verses are included):

Several things are clear from this table:

the distinctive d flat appears in the first phrase, never to be heard again;

instead, the phrase ends on four different tones – incidentally each of the four different tones in the Gm7-5 chord;

any trace of rhythmic regularity is missing;

the phrase is never sung the same way twice;

and last but not least: the clear wave structure from Bing’s version is gone, replaced by variations over a skeleton consisting of the tones f–a–g–f (marked in red), in that order, but realised differently every time;

It is interesting to note just how differently it is realised. This is actually one of the things that has fascinated me most about Dylan’s phrasing and singing style: how he manages to pick tones that both sound random and at the same time completely regular (only not, perhaps, according to any common rules). If you try to mimic it or copy it, it can actually be quite difficult sometimes, but once you put it on paper, it just looks banal – so banal that you look like an idiot who didn’t see it right away. Dylan stays within – or rather: relates to – a certain framework all the time, but within that framework, he can end up in very unusual places, though the ryhtmical micro-shifts, through slight variations in emphasis of the skeletal notes (see for example the “we feel and we think” line), or a grain of uncertainy (such as the “feel” in that same line).

See for example how the phrase above ends on three different notes only in the first verse – d flat, f, and a, the first following Crosby’s version, the others starting in the same g–f cell (“toils”, “know not”, and in the second verse: “haunted” and “shadows”) – and we still perceive it as the same phrase, somehow.

If we turn to the second part of this phrase, Bing’s version could be heard as an inverted echo of the ti-ti-taaas of the first half, going in the other direction both melodically and rhythmically (ta-tiiii, ta-tiiii, taaaa):

Dylan’s changes are perhaps even more pronounced here:

Again, he follows Bing closely the first time around, but that’s where most similarites end. If we reduce Bing’s version to its barest minimum, what remains is an f–g–f structure with c as a recurring “anchor”. Dylan keeps the f–g–f figure, but eventually the c anchor gradually disappears, and another tone, a, enters the picture and more or less takes over the structural role of g in the phrase. G is reduced to a passing note in the final descent from a to f. In the last line of the second verse, the transformation is complete: a dominates, and c is gone.

This actually means that the second half of the line, which started as a contrast to the first, gradually morphs into a reflection of it, using the same f–a–g–f skeleton.

Rhythmically, too, the contrast is gone. In the first verse the short–long rhythm of “someone” are preserved, but it disappears more and more , and the second verse is all over the place.

Hearing the two tracks side by side, it is obvious that Dylan’s song is “based on the melody from a Bing Crosby song” – it’s as if Bob is singing harmony with Bing – but note for note it is most of the time difficult to find direct identity between the melody lines.

And this is where the comparison with Bing Crosby’s version is most interesting: not as an exhibit in a court case about plagiarism, but as an insight into Dylan’s style: what he does, why he does it, and why it is so interesting to listen to.

I’ve hinted at it: the constant micro-changes, and the gradual transformation of the underlying logic, while still preserving the sense of coherence. This is what I have elsewhere referred to as Dylan’s way of creating a body in sound.

The third line: “If onlyyyyy aaaai could seeyouuuu”

If the first line can be regarded as different realisations of the same structure, with the third line it’s the other way around: note for note the two versions are identical, but the character of the outcome is quite different (see the music example and soundclip above).

Bing slows down the rhythm, from repeated ti-ti-taaas to an even more contemplative ta ta-taaaa, taaaa, ta ta-taaaa (“If onlyyyyy aaaai could seeyouuuu”). Dylan, on the other hand, has more on his mind and turns the two-phrase line into three dense lines of text, thus making this phrase conform with the metrics of the rest of the stanza.

This is actually a peculiar aspect of the song: why would Dylan choose to “mess up” the verse structure of the original song, by removing the contrasting character of the line and assimilate it with the surrounding phrases?

There are some possible solutions:

He actually wrote the lyrics first, and made them fit the song once he decided to match them. This is actually not an entirely silly option, and it would explain the levelling of the structure.

He simply wanted it like this – to avoid the contrast and instead work with the material from within a coherent phrase structure.

It is part of Dylan’s long-term work with song forms, where the distinction between large-scale and small-scale form is blurred.

This last option is the one I lean most strongly to. If there is one novelty that characterizes Dylan’s work over the past many years – at least since Cross the Green Mountain, and culminating on Rough and Rowdy Ways, it is the large-scale song form where the function of the refrain is up for discussion, where several verses form mega-verses (e.g. “Murder Most Foul”, which I’ve discussed at length elsewhere), where verses tend to become longer, so that the internal structure of the verses come to take on the characteristics of a whole song.

In Bing’s song, it is as if each three-line block is a verse of its own: they are some times replaceable, played (or rather: whistled) as a solo here, functioning as a full refrain there. The two-line third section, then, takes on something similar to a bridge function: a B section with a contrasting character, ending on the Dominant.

By assimilating the phrase structure between the two main phrases, Dylan says: “This is a verse, a full block of music, and nothing else. If there is to be a solo – which there is – it belongs between these verses, not in the middle of them.”

All in all: melodic and harmonic similarity do not equal musical identity. An interpretation based on harmonic progression and underlying melodic structure, would judge the two versions to be virtually identical, but the musical logic behind them are radically different, even down to the fundamental building blocks of verse and refrain, which also means that the musical objects that come out of this, may in fact be more different than they may seem at first glance. When the Deal Goes Down is a song which, although based on Where the Blue, on important points is entirely new: there is some creative input in it, it is based on a different musical logic, there are clear traces of Dylan’s very own phrasing – it is distinctively Dylan and not just a new set of lyrics to a stolen melody.

At least that is what the apologetic reviewer would argue. One thing is missing from his argument, though: most of the above could be said about Dylan’s Sinatra covers as well, which I praised in the issue about Shadows in the Night: he brings in his own distinctive phrasing, the personality of his voice, etc., but that doesn’t make it a song written by Bob Dylan. Musically speaking, When the Deal Goes Down is Dylan’s cover of Where the Blue of the Night, sung to his own new lyrics.

So my qualms with the labelling of this as a song (which must mean: text and melody) that is “Written by Bob Dylan” have not gone away, but I deeply enjoy it all the same, both as yet another insight into the musical brain of Bob Dylan, and as a song in its own right – which most of the time I prefer to hear sung by Bing Crosby. But then again: I’ve always been a sucker for Jiminy Cricket.

This text is partly based on a section in a blog post about the various accusations of plagiarism that have been directed against Dylan over the years. It has been substantially rewritten and expanded, however.

Lyrically and musically he has been a collage artist for a long long time.

That is true, although in many different ways over the years, some more palatable, others more on the dubious side, both aesthetically and even legally, I would say. I draw a sharp line between plagiarism and collage art, and that line is quite clearly illustrated by the two areas in which accusations have been made: the musical and the lyrical. I think the borrowings from Timrod and Ovid and guide books from New Orleans and what not (and in earlier years: from movies and from nursery rhyme) are potentially quite fascinating. Musically, though: to lift a whole arrangement is not collage. At best, it is intertexuality, at worst - well: theft.