Dylanology No. 4 (2021/8) - Shadow Kingdom - The poetics of Mr. Tambourine Man - and more

1: The “Rumpnisse” Mindset: Why does Dylan do what he does? - 2: Prelude to poetics: Approaching Mr. Tambourine Man - 3: Shadow Kingdom - 4: You Ain't Going Nowhere - But why?

The “Rumpnisse” Mindset: Why Dylan does what he does

Dylanology has now reached its fourth issue. Eyolf Østrem sits back and reflects on what the project is really all about.

Eyolf Østrem

So far in Dylanology I’ve written quite extensive and detailed analyses of one album (Highway 61 Revisited), one performance (the version of “Jokerman” from the Letterman show in 1984), one lyric rewrite (the development that turned “Too Late” into “Foot of Pride”), and one entire show (Shadow Kingdom).

Those texts have two things in common: an almost obsessive attention to detail and technical description, and attempts at making very general, far-reaching observations and conclusions, not only about the concrete objects of study, but about Dylan’s music making in general, about his art in general, and about the world in general.

This may at times result in texts that are hard to read, especially if one is not a fluent reader of sheet music or if music theory is not one’s first language. Jakob Brønnum, in his readings of Dylan’s lyrics, has written with similarly obsessively detailed analyses of their metaphors and their points of reference to a wider cultural tradition.

This is, however, a very conscious choice, based on a certain conviction about what good analysis should do. I think of it as the “Rumpnisse” mindset.

Annoying and at times dangerous

The “Rumpnisse” is a certain species of gnome who appears in Astrid Lindgren’s book Ronja the Robber’s Daughter. They are very annoying – at times dangerously so – in their incessant questioning: “What is she doing? Why does she do that? Why does she do it in that manner? Why so, then?” And so on.

Bob Dylan has always been a Rumpnisse: he has constantly been asking those annoying questions: “How many roads?” “What did you see? What’ll you do now?” “How does it feel?” “Do you love me, or are you just extending goodwill?” “What was it you wanted?” “What’s a sweetheart like you doing in a dump like this?” “Whatcha gonna do when the shadow comes creeping in your door?”

But that’s not the main reason for using the Rumpnisse mindset. I consider it the only methodology one needs in the humanities, including Dylanology.

What every analysis is after, after all, is an answer to some version of the question: “Why does he do what he does, in the way he does it?”

This question can be transformed in to several other questions and assumptions when it comes to art:

It is all about human activity, one human being doing something that another human being finds rewarding. “Why is that?” is the Rumpnisse-question.

It is a matter of intention: someone does something with the intention of achieving a resonance in someone else. The Rumpnisse observes a “what”, then asks “Why?”

It is a question of meaning, in both senses of the word: it feels like a meaningful undertaking for both parties to enter the relationship, because they both sense that something, a meaning, is being transmitted.

What is perhaps obvious but still is worth pointing out is that on all points, something specific, something physical, concrete, observeable is being done, be it movements and gestures on a stage, or pulses of compressed air forming sound waves, some of which are recognized as chords and melodies, others as words and phrases.

Emotion and meaning don’t just emerge miraculously out of genius and thin air; they are enticed, brought out, created, molded, from clay or from pigmented oil smeared on potential bed sheets or from plucked cat guts strung across pigskin, or whatever medium the artist has found to be suitable means to transmit his perception of the world to the rest of us.

Those are the details and physical roots that the Dylanological explorations seeks to find. The procedure goes: observe what is being done; lay out the framework in which it is presented; search for the underlying experience or emotion that is being expressed in this framework; see if it resonates beyond the concrete action and framework; and that’s what it means.

The Meaning of Music

Everything above is complicated further because it is music we are talking about.

The question of what music means is hardly meaningful without the more precise question how music means.

The former question is senseless: music doesn’t mean anything, because meaning is tied to concepts, words, language, but there is a how to music, which makes it resemble meaning.

In a way, it is much easier with language: the shortcuts from sound waves to mental image are much more firmly established, so that we rarely feel compelled to ask: “yes, but what does it mean?” if someone says “cat”.

But this is where music can instead gain the upper hand: since it feels meaningful even though it perhaps isn’t, it prompts exactly that question: even though someone may quite accurately point out that, clearly, what you’re hearing is just airwaves that taken together form a C major chord – still “yes, but what does it mean?” is a perfectly valid and much more sane response.

Art and the Human Condition

The line of reasoning and questions goes something like this:

Hey! What just happened there?

What did he just do?

How did I experience it?

What does it mean?

Perhaps it is fair to say that one person’s experience is just that and nothing more: one person’s experience. Only when it is communicated to someone else and it resonates there can we say that it means something, whether it is a word that means “cat” or a chord that means “C major” or “fulfillment”. If so, the question about meaning can be rephrased into the much simpler: “How did you experience it? Same way as I did?”

And at the end of the line:

That’s why!

That’s what happened!

That’s why I felt what I did.

And if that experience is shared, the investigation is no longer about single experiences, but about the human condition and our means to express it.

Dylanology is about writing cultural history at the level of individual detail. The point behind the focus on details, nerdy as it may seem, is not to dig out as obscure factoids as possible, but to point out a specific understanding of our shared experience of the world and anchor it in observable facts.

This is also what sets Dylanology apart from its predecessor, “garbology”. When A. J. Weberman dug through Dylan’s garbage back in the 70s, his goal was to figure out something about Dylan. When I dig through outtakes and listen for barely audible guitar parts in old concert tapes, my goal is to figure out something about humanity, through the lense of my own reaction to Dylan’s placement of his fingers on the fretboard of his guitar and the sounds that that produces.

I am not interested in Dylan as a person, but in the way he presents his perception of the world, distilled into specific actions and shaped into a stylized form, so that we, the listeners, are given tools to recreate that world in our image.

That is, I would say, what the artist does, and by doing so he gives us the opportunity of a shortcut, both to the perception of another human being, and possibly to the world and ultimately back to ourselves.

Big words, but that’s what Dylanology all about. So bear with me if at times it feels as if I’m dissecting the lab rat and burying it under heavy terminology and tangles of words. I am after all just another Rumpnisse.

Prelude to poetics: Approaching Mr. Tambourine Man

Jakob Brønnum

It is well known that Bob Dylan left the folk music revival movement some time between the recording of the album The Times They Are A-Changing August 6-October 31 of 1963 and the performance at the Newport Folk Festival on the 25th of July 1965, his first electric performance, with members of Paul Butterfield Blues Band.

It is less clear exactly why Dylan moved away from political song writing, which he did already on the 1964-album Another Side Of Bob Dylan with its distinctly different profile from The Times They Are A-Changing.

In this text I shall argue that he did so not the least because he felt his artistic development severely constrained in the folk movement. As with all the readings I attempt here in Dylanology the focus is not on what Bob Dylan might have said, thought, felt, or meant, but primarily on what one can read in and out of his actual lyrics.

The times that changed

A lot of possible reasons for Dylan changing artistic direction at this time have been given. One is that the political and human tragedy that occurred between the recording of The Times They Are A-Changing and it release in early January the following year, changed everything; that the murder of President Kennedy in November 1963 made it clear to the young folksinger that folk music would never be able to achieve peace and equality among men. A small scandal occurred when Dylan in the acceptance speech of the "Tom Paine Award" from the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee shortly after the assassination of John F. Kennedy claimed to see something of himself and of every man in Kennedy's assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald. After which he left the banquet. People around him have described this as Dylan being in a state of chock and resignation.

A closer look into some of the songs on the two albums recorded in 1964 and 1965 during the time of the break, reveals a pattern of critique against the movement and its dogmatism and political correctness (an expression that didn’t exist at the time). Dylan seems to explain in song what is going on in his songs.

What really is going on at Maggie’s Farm

“Maggie’s Farm” is one of Dylan’s all-time popular electric blues-rock songs. The lyrics to the song are understood very differently. The Wikipedia article sums it up by quoting several critics assessing them to be about how the ’narrator feels held down by the record company or industry or any other big time player preventing Dylan’s true art from flowering:

I got a head full of ideas

That are drivin’ me insane

It’s a shame the way she makes me scrub the floor

I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s farm no more (verse 1)

The song plays through the moral double standards of various members of Maggie’s family – the father, the brother, the mother. One is more autocratic and despotic than the other:

I ain’t gonna work for Maggie’s brother no more

Well, he hands you a nickel

He hands you a dime

He asks you with a grin

If you’re havin’ a good time

Then he fines you every time you slam the door (verse 2)

The verse about the money could be what leads people to associate to the music industry. But other verses evoke other metaphorical images all together. It is a very bitter-sounding song in which everything takes place within a very small world of a farm where the narrator is working, more or less voluntarily.

What the song’s title alludes to is not quite clear either, according to the critics and commentators. Though Howard Sounes in his Dylan biography mentions a “Maggiore’s farm” that Dylan allegedly drove by in New York State, it seems sobering when elsewhere Silas McGee's Farm, where Dylan performed at a Civil Rights rally in 1963, is brought up.

As quoted above the narrator alludes to a creative burst that he cannot freely follow because he has farm- and housework to do. The first verse begins with a brilliant piece of sarcasm:

Well, I wake up in the morning

Fold my hands and pray for rain

I got a head full of ideas

That are drivin’ me insane

It's a shame the way she makes me scrub the floor.

He prays for rain seemingly because that’s what you do on a traditional farm. But this is not why our hero does it. He does it so he can stay inside and write. But alas! Even when farm work is suspended, he is not left alone, but has to scrub the floor. The song is about how the expectations you are met by and the duties you have at Maggie’s Farm is holding you down. If “Maggie’s Farm” alludes to the folk revival movement or the civil rights movement it offers a kind of an explanation as to why Dylan left.

If you think you are so clever …

“My Back Pages” is populated by the same kind of clientele and mindsets. Now the cast is not family members, they don’t play the traditional roles you play in an hierarchical farm community. They play roles in society as such, they are a professor, a soldier, a political activist, you hear about the expression of prejudice, primitive political arguing (“lies that life is black and white”). It is a song that rejects all of the same kinds of mind games that lead not to freedom but to the kind of slavery we met in “Maggie’s farm”. Its timeless one-liner refrain speaks about a change of a condition of consciousness seemingly against nature:

Ah, but I was so much older then

I’m younger than that now

How can you grow younger? Of course, you can’t grow younger, but in your mind you can, if you realize that truth or art or life itself is not something you perform from stale political views formulated once and for all. They are something you have to always seek out in order to remain open minded, young at heart. The young Bob Dylan without much doubt realized that for these reasons he could not remain part of a movement.

Poetry, freedom, and surrealism

“My Back Pages” expresses this even in the way it uses the poetical language: In the folk music revival that Dylan joined when he came to New York in 1961 there was a connection to a left wing political worker’s movement, leading to a form of mandatory asceticism in the use of lyrics and musical form, as well as (acoustic) instrumentation.

“My Back Pages” is clearly not a folk song. It is surrealistic and would be heard in the movement as elitist. It wouldn’t be understood by the common man. Two albums further up the road, it is all surrealism in some form, as on Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde.

But how to achieve freedom in your own writing? This is what Bob Dylan sets out to explain in the mighty “Mr. Tambourine Man”.

“Mr. Tambourine Man”, which opens the acoustic B-side of Bringing It All Back Home, is a song about the artistic process. Obviously to most listeners it is about drugs - with “the smoke rings of my mind” as a metaphor for marijuana and the “Take me on a trip upon your magic swirlin’ ship” as experiences with LSD.

As Andy Gill writes: “To impose such a narrow interpretation on the song is to miss its wider meaning, which has more to do with the artists invocation of his/her muse (here confusingly cast as a male figure, rather than the more usual female.”

Dylan’s Ars Poetica

In the next four short pieces I shall try to show that Mr. Tambourine Man is in fact a form of Ars Poetica, an attempt to explain not only what art is, and how you go about sharpening your senses to pick it up and pen it down. But also a diatribe about the relation between art and existence. The four monumental verses each deal with phases of creative writing:

1. The experience that your writing doesn’t work. You dream up something you feel is going to be great (“that evenin’s empire”), but the next day you see it was nothing but a sandcastle (“has returned into sand”)

2. The poet realizes the unfruitful situation with loss of creativity (“my senses have been stripped”) and makes the difficult choice to leave his own petty ideas and formulas (“I’m ready to go anywhere”) and listen for the thing itself

3. The acknowledgement of the fact that he might not succeed at first and looks like “a ragged clown” chasing his own shadow.

4. The arrival at a state of mind where he is free in his writing (“Yes, to dance beneath the diamond sky with one hand waving free”) while listening to a form of higher poetical-existential creativity that may take him anywhere.

Read in this way it obviously stands out like a practical poetics – an artist’s description of his art and of the conditions for creating it. Probably nowhere else – maybe with the exception of part of “Highlands” (Time Out Of Mind), Dylan interacts so closely with the creative process as in this poetical masterpiece.

In the coming issues of Dylanology I shall try to follow this process in detail, verse by verse – and there really is much more detail in Mr. Tambourine Man casting light upon the creative process than I’ve touched upon here.

Besides, it is still necessary to try to define what the tambourine actually alludes to, metaphorically. We know Dylan refers to a giant tambourine-like instrument (a Turkish frame drum) played by the guitarist Bruce Langhorn at the time as the inspiration for the title. But what is the impact of the tambourine-metaphor? And there are more questions: Why does the song open with the refrain? It is Dylan’s only song to do so.

The Kingdom of the Shadowy In-Between

A Review of the cracks that make Shadow Kingdom Dylan’s most interesting musical work

Eyolf Østrem

The pandemic brought an end to the Never-Ending Tour, but it could not stop Bob Dylan’s constant, creative outpouring. The monumental “Murder Most Foul” grew into an entire album, which turned out to be one of his best ever, and on 18 July 2021 we finally got what many of us had been waiting for: new live material, streamed to anyone who wanted – in itself a revolutionary new concept.

It wasn’t live, of course. It was a film noir, prerecorded and presented so as to look like a live performance. Much has been said and written about the presentation, the acting, the musicians, and the assessment of what path Dylan is on at the moment, post-NET, post-MMF, post Corona.

As a Dylan fan, I find all these aspects interesting, but as a musicologist my primary interest is: what is he doing musically? It turns out that Shadow Kingdom is in fact a highly interesting and intriguing work of musical art, especially in the carefully elaborated transitions between the songs – the Kingdom of the shadowy in-between.

If you haven’t watched Shadow Kingdom yet, I recommend you do so. Guitar tabs and lyric transcriptions for most of the song versions are available on dylanchords.com

Harmonic Cohesion

“Cohesion” is a word from Latin which means to stick together. It has never been high on Dylan’s agenda, harmonically speaking. I have discussed this on several occasions before: Dylan avoids the Dominant, and especially the dominant seventh – precisely the chord types that more than any create cohesion. [A music theory footnote here: I use “tonic” as a synonym for the keynote, “dominant” = the chord on the fifth scale step (so in C, the dominant is G), and “subdominant” = the chord on the fourth step (F).]

Then came his long love-relationship with Sinatra songs, and these are all about harmonic cohesion: the natural transition from one chord to the next, based on the resolution of tension and on perceived melodic lines, not just in the tune itself, but in all kinds of middle voices, heard or just imagined, implied.

The question on everyone’s mind during the never-ending pilgrimage through the Sinatra catalogue was: what would it lead to? Would we see Dylan writing jazz ballads and big band pop?

As I indicated in my reviews of the Rough and Rowdy Ways songs, it is not that the Sinatra influence is obvious, but there are signs, most prominently in “Black Rider”, Dylan’s most complex song ever.

Coming Over Here From Over There

Some of the songs from the most recent years of touring were played in arrangements that demonstrate a hightened sense of harmonic cohesion (in the next issue of Dylanology, I will discuss “Tangled Up in Blue” from this perspective). This is not the case with Shadow Kingdom, where the arrangements are, if anything, simplified, rather than more complex.

Nevertheless, Shadow Kingdom may well be the most interesting piece of music from Dylan’s hand in a very long time, primarily because of what happens where we usually don’t look, in the intermediary doodlings in the shadows between the songs.

In this sense, it is worth regarding Shadow Kingdom as one coherent piece of music, where cohesion is at work not so much within as between the songs. The transitions, despite their fleeting, ephemeral character, are actually worked out in great detail, at times emphasising harmonic relations that exist in the songs themselves, other times concealing the interrelations, fooling us to believe we are on firm ground when we are not, and consistently working with a small number of motifs and patterns and with the order of the songs and the keys in which they are played.

I will go through Shadow Kingdom with this in mind, completely disregarding the singing, the acting, the filming, focussing only on the interludes, the way cohesion is created, and the patterns that are used to this end.

Same Key:

From “Masterpiece” to “Most Likely”

The simplest possible kind of cohesion is heard between the first two songs: stay in the same key. “When I Paint My Masterpiece” is played in G and ends with a very elaborate ending:

After a brief silence, the next song begins in the same key – the easiest way to create harmonic cohesion: keep on doing the same.

Same key? Really?

But even this is not as simple as it may seem. The next song is “Most Like You’ll Go Your Way And I’ll Go Mine”. This is one of several songs in Shadow Kingdom that plays with the simultaneous use of major and minor versions of the same chord.

In the center of the original version, from Blonde on Blonde (1966), stands a harmonica riff where the “blue third” – somewhere between major and minor, both and neither – is prominent.

Here, however, it is played by accordion and strummed guitars, and they have to choose one or the other. The way the riff is played, there is a constant shifting back and forth between G minor and G major, with a slight emphasis on the minor version. This is particularly evident in the very beginning, where the contrast with the very clear and emphasized G major of the final chord of “Masterpiece” stands out.

With this in mind, we may go back to the “Masterpiece” ending and notice that the same contrast is actually present there: the stop-and-start accordion motif in the first measure of the example above (marked in red) has no clear tonality, since the third is more or less left out, and when the mandolin enters the third time the motif is played (blue), it has exactly the same bluesy ambivalence between b/b flat, and f/f sharp that becomes the main topic of the next song.

But there is more: after the mandolin motif, the guitar (possibly Dylan’s own; marked in green) enters with a slowly descending scale motif which ends by going to E minor instead of G major – a so called deceptive cadence, which exploits another kind of ambiguity between a major and a minor chord, this time the closely related parallel chords Em and G.

So already in these few bars of interlude we have the seeds of a musical large-scale structure.

Dominant preparation:

From “Most Likely” to “Queen Jane” and “Baby Tonight”

The next transition is done with no particular preparation or elaboration: after the final G major chord of “Most Likely”, “Queen Jane Approximately” starts in D major:

But between “Queen Jane” and “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” there is again a lot going on.

The last tones of the melody in “Queen Jane”, played on the harmonica, are taken over by the accordion and the other instruments, over a rhythmless D major chord. The tonal contents of this chord shifts and shimmers, touching at a D7 chord here, extending it to a D9 there, until a slow and broad A7 chord is played.

Since A is the dominant of D, and the seventh chord is strongly associated with the dominant function, we are doubly expecting a return to a final D major chord to end the song on the keynote:

G F#m Em A D | A7 → D

But we are deceived: it turns out that A7 is not the Dominant of D major, but the keynote of the next song.

And, again: in hindsight we may be reminded that that is exactly the relationship between the previous two songs, where “Most Likely” uneventfully gave way to “Queen Jane”: D is the dominant of G, just as A is the dominant of D. The difference is that this time we get the added “trick” chord A7 (with the implied resolution in brackets).

2–3: G | D

3–4: D – A7 [→ D] | A

So by now we seem to have established two motifs: the ambiguity between major and minor chords (including the minor and major seventh), and the deceptive dominant relationship between songs.

In the next transition, both these themes come into play. “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” ends as a slow blues on a rich A9 chord with the four tones of the seventh chord clearly outlined by the accordion (marked in red).

Now, an A7 in this position would either be the final chord of an A blues (since it is a genre specific convention of blues songs to add a seventh even to the tonic chord), or – if it is perceived to lead somewhere else – a dominant seventh to D major.

Not so this time. Right in the middle of this full, delicious A7 chord, the guitar (which again I presume is played by Dylan) plays a little figure g#-a-g#-a (marked in green), tentatively, almost as if he is just stumbling upon it as a doodle to embellish the A sonority. The g# in this figure clashes strongly with the g natural of the A7 chord – again the major/minor pattern.

There is still no indication that we have left the key of A, however. Not until the accordion picks up this little figure and turns it into a melodic motif by extending it down to e and adding a typical bluesy g-g# flourish, so that it becomes a melody in E major (marked in blue).

E is the dominant of A, so if we expect anything particular at this point, it would be a return to A again. But we get no such return.

If this sounds familiar, it is because it is exactly what has just happened a couple of times before: the song ends with a turn to the dominant, which turns out to be the new tonic. Looking back, we may notice that each new song has had an added sharp: from G to D, A, and now E.

This time around things are being complicated further, however. According to the now established pattern, where a dominant becomes the new tonic, we expect E major to be the new keynote. But the first chord we hear is in fact B major, with an E as a quick “grace chord” (marked in brown).

Are we being tricked again? In a way, yes. The trick this time is that the intro of the song does not begin with the keynote, but with the dominant. Only a couple of chords in do we reach the keynote, which is indeed E major. We are tricked into believing that we have been tricked, so to speak.

Cliffhanging:

From “Tom Thumb” to “Tombstone”

After this sequence of song transitions, we would expect the next interlude to lead us from E major to B major. So let us see what happens:

“Tom Thumb” ends the same way it starts, with a very plain cadence figure (B6–A6–E), which is repeated a couple of times and ends with a reversal of the “grace chord” from the beginning (again marked in brown; there, we had E/b–B, now: B–E).

Rhythm then dissolves and we get a slowly strummed E major chord, followed by … F7! Not the B we had expected, but as far from that chord as it is possible to get, since F and B are a tritone apart. Tricked again!

The F7 chord is played as an echo of the E chord that precedes it, with the same embellishment and style. Maybe that is a sign that F is the new keynote? At least the next chord after F is C major, followed by Bb major, and again those two chords are tied together by using similar figures in the guitar.

C and Bb happen to be the dominant and subdominant in F major, and they function the same way as the B–A–E pattern from “Tom Thumb”, so our new theory holds: we are heading back to F again – until it becomes clear that we are not.

Of course! That is the revised pattern: create an expectation of a return to a tonal centre, then stop on the edge of the cliff and take it from there. “Tombstone Blues”, then, is played in Bb major instead of B major.

Out of Pattern:

No Connection

After “Tombstone Blues” there is a full stop – much longer than between any of the other songs – and no attempt at a transition. The next song, “To Be Alone With You” begins, out of the blue, in E major:

Clearly, we are out of the pattern. “Tombstone Blues” can be seen as the end of the first set of the concert.

A Half-Time Evaluation

The way the same patterns are being presented, employed, gradually changed, expanded, is clearly recognizable as the way harmonic development is treated in the classical tradition.

But it is also perfectly consistent with Dylan’s own music making, as I’ve discussed previously in connection with his remarks about “mathematical music” in Chronicles: his way of establishing a pattern, perhaps even a random one, and then sticking to it, modifying it, playing with it, and letting things happen.

Reversal:

From “Alone With You” To “What Was It You Wanted?”

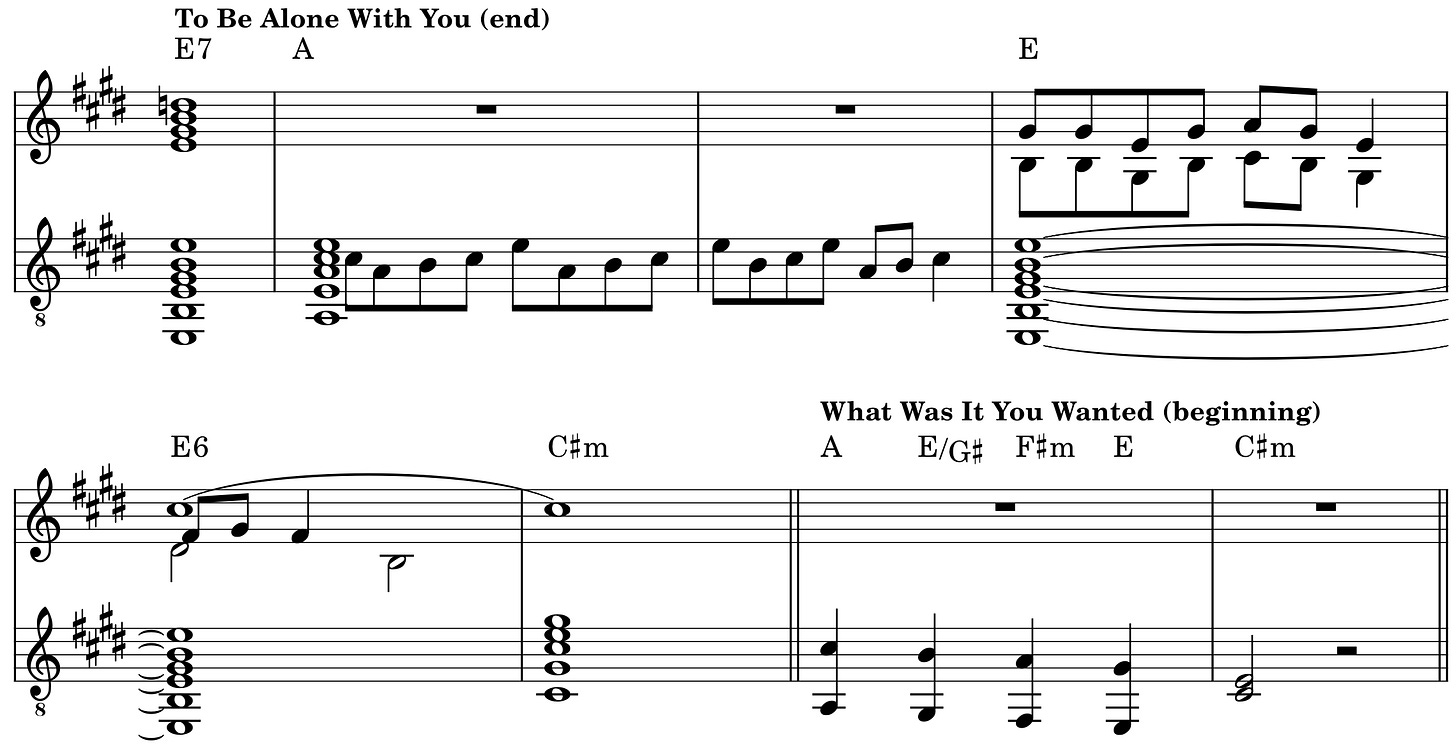

“To Be Alone With You”, then, can be seen as the start of the second part of the concert. And when it ends, it may seem as if we are back in known territories:

After the final E7 chord, A major is played, and since the pattern is: “create expectations of a return (here: from A to E) but instead continue from where you are,” we would expect the next song to continue in A major.

But for the first time, just when we are beginning to expect our expectations to be deceived, we actually do get a return to the expected tonic, E major!

The trickster strikes again!

But now the second of our two patterns comes into play: the major/minor switch. This time it is not the variant on the same keynote (E/Em) but the relative minor, (E/C#m), that is the target, and indeed the keynote of the next song, “What Was It You Wanted?”.

This is, we may remember, the same chord relation that was introduced in the very first song, “Masterpiece”: the deceptive cadence.

Simplification: From “What Was It You Wanted?” To “Forever Young” to “Pledging My Time”

“What Was It You Wanted?” begins and ends with a distinctive motif, a descent in parallel tenths from A back to C#m again (my insistence on writing only about the interludes forbids me from mentioning that the way this motif is extended the last time it appears, starting higher and spanning the entire octave, is one of the truly satisfying musical moments of the entire show):

When the song ends, on C#m, the transition starts with D7. This is the same trick that was used between “Tom Thumb’s Blues” and “Tombstone Blues”: shift everything up a semitone (there: from E to F7). We seem to be going backwards through the same tricks that were used in the first half of the show, in a mirror movement.

But each of the “reflections” are treated differently. This time, we first go back again to C#m – another novelty, since going back to where we came from, as we have learned, is not something we do – then the shift to D is repeated, and we are in our new key – simple as that.

Even the next transition sees simplification. After the final D major of “Forever Young”, there is a long A7 chord with lots of embellishments. Toward the end of this prolonged chord (in fact the longest in any of the interludes), a triple time blues lick is introduced, and this is indeed a direct introduction to “Pledging My Time”.

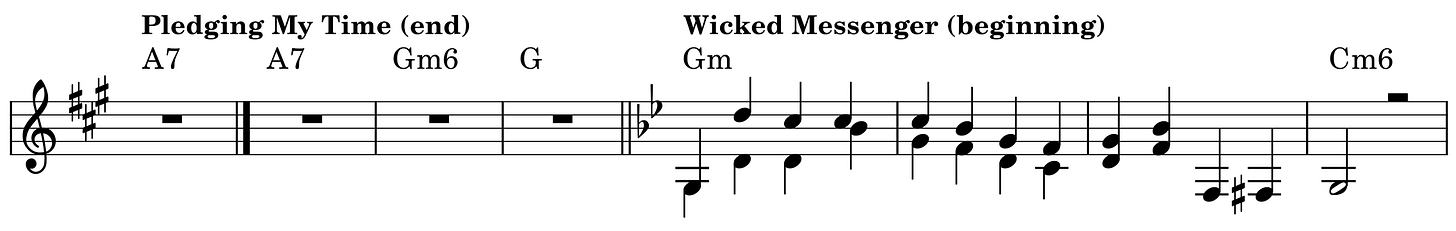

Wicked Pivoting: From “Pledging My Time” to “Wicked Messenger”

“Pledging My Time” ends with a standard blues turnaround ending on A7. Where to go from here? So far, we have seen the equivalents of E, D, and Bb.

Instead we get Gm6.

What is Gm6 – a chord far over on the flat side of the harmonic spectrum – doing here in A7, a key far to the sharp side?

Well, two things, potentially. First, even though the chords are far apart, they do actually share two notes. The keynote of Gm6 is the g that turns A into the seventh chord A7; and e, which makes Gm6 a sixth chord, is an essential part of A major.

Such shared ground indicates that there is some connection, and indeed: A7 and Gm6 would have been perfect together had we been in another key altogether: in D minor. There, they would have represented the Dominant and the Subdominant, respectively.

So is that where we’re heading this time – to D minor?

It turns out… it’s not.

Again, there are tricks. This time it’s the major/minor switch. The ambiguity that was introduced in “Most Likely”, the second song of the concert, comes to full bloom in “The Wicked Messenger”. Here, there is not simply ambiguity: the two chord variants are frequently played at the same time, on top of each other – no longer an alternation but a combined G major/minor. So after A7 – Gm6, at the point where we are somehow expecting a return to A7 or a transition to Dm, Dylan instead goes straight to G major, then begins the song in the joint G major/minor.

Resolution At Last? From “Wicked Messenger” to “Watching the River Flow”

In the end of the song, there is again the major-minor switch – and now comes the Dm we were led to expect in the former transition. So now is that where we’re heading?

Of course not. And there is no end to the deception. The Dm chord is played sandwhiched between Gm and A – exactly the environment which led us to expect it the last time around. The sequence

Gm – Dm – A

would very naturally lead back to Dm again, since that is the tonic that the chord sequence implies, so of course Dylan goes somewhere else: to B major! The chord that would have been the culmination of the harmonic progression in the first half of the show, but which was deceptively changed to a B flat major in “Tombstone Blues”! Are we finally reaching resolution?

It would seem so: the beginning of the passage sounds like a picture-perfect twelve-bar blues in B major: two bars of B riff followed by two bars of E7 riff – all set for a return to B again.

But of course we’re not going there. Instead, Dylan stays on E, which is only now revealed as the real keynote of the next song, “Watching the River Flow”. Tricked again, this time even more elaborately, since the B major section is so long and so credibly in style.

Once E major has been established as the key, this retrospectively explains the abrupt step from A major to B major a few bars earlier: In the old context of G minor (in “Wicked Messenger”), B major arrives out of the blue, totally unexpected; but in hindsight, in the new context of E major, the chords A and B are simply Subdominant and Dominant – a perfectly natural and happy relationship.

Strike Another Match:

From “Watching the River” to “Baby Blue”

The weirdest transition has been saved for last. “Watching the River Flow” ends in blues style on an E7 chord, slowly strummed, then forcefully ended. After a brief pause, the next chord is G6. Then follows C# minor. What is going on here?

The three chords have a few things in common. The tone e runs through them all. E7 and G6 also have the tone d in common, and E and C#m are relative chords (the alternate version of the major/minor pattern again).

All this is swept aside with the next chord, however – a true “You won’t believe what happens next!” clickbait moment. The one stable, common element, the tone e, is raised a semitone to e#, and all of a sudden we are in the rare key of c sharp major!

The major/minor trick again, in the crudest, wildest fashion, reminiscent of Beethoven. The direct introduction of the major third, e#, especially after the minor third, e natural, has been so thoroughly prepared, creates an ethereal, shimmering sonority, completely new, completely heavenly.

My final observation may be far-fetched, but bear with me: I’m just the guy who tries to make sense of chord progressions. The question I’m wrestling with is: why this shift, and why that preparation, through G6?

Here’s an idea: Those familiar with “Baby Blue” as played in its most common key, C major, will recognize the two chords G and E.

G7F C You must leave now, take what you need, you think will last. G7 F C But whatever you wish to keep, you better grab it fast. Dm F C Yonder stands your orphan with his gun, Dm F C Crying like a fire in the sun.EF G7 Look out the saints are comin' through Dm F C And it's all over now, Baby Blue.

G is the key the song begins with (since this is another one of those songs that don’t begin on the tonic but on the dominant), and E is the climactic chord at “Look out!” and “Strike another match” – the emotional highlight of verse after verse of the song.

In C major, E is the chord a major third up from the keynote.

Now consider this: the key of “Watching the River Flow” is E major. The chord a major third higher is G sharp major – which is the chord that “Baby Blue” begins with. So not only is C# major introduced in glowing beauty – but the climax within “Baby Blue” is recreated between the two songs.

And while we’re at it: G lies a minor third up from E; C# a minor third down from E. Wherever we look there are these relationships between major and minor versions of the same interval, in this case the major third at “Strike another match”, the most emotional interval in the last song of the set – the song that begins: “You must leave now” and ends “It’s all over now”.

Can This Really Be The End?

So, is it? Is this really the end, as some have speculated? Is Shadow Kingdom Dylan’s farewell to touring?

If it is, the transitions between the songs are a remarkable testament, transforming the three-chord folkie into a sophisticated composer who for the first time is carefully crafting chord progressions heavy with meaning and strong cohesion.

And if it is not, then we surely have exciting times ahead.

“You ain’t going nowhere” - But why? Because everything is already here

One of the most charming and humorful events around the universally celebrated birthday in May when Bob Dylan turned 80 was when the cast from the Belsco Theatre musical Girl From The North Country performed You Ain’t Going Nowhere on the streets of the city. (The musical was the last to open on Broadway before the pandemic shut down. It will resume on October 13)

You Ain’t Going Nowhere belongs to the category of Dylan songs which also comprises some of his most overwhelmingly popular ones: two, three, four short verse and a refrain. It is songs like “I Shall Be Released”, “Knocking On Heaven’s Door”, “Make You Feel My Love” and “Ring Them Bells”, as well as “Blowing In The Wind”, “Tomorrow Is a Long Time” and “Forever Young”.

But “You Ain’t Going Nowhere” doesn’t hold the position of the others in the canon. Why not? It is not so easily relatable as the others to basic sentiments, dreams, and struggles in life. It is a surrealistic song with not so straightforward reference points, more or less devoid of specimen of Dylan’s unforgettable one-liners. To tell the truth, nobody knows what he is talking about. Maybe Dylan isn’t talking about anything at all and the charming lightness of the song draws on its poetical nonsense in the vein of Lewis Carrol or the literary genre called Nonsense Verse.

No nonsense

But it isn’t all nonsense, of course. It is surrealism with a cluster of metaphorical philosophy of existence marking out one of Dylan’s most solemn insights: That life is always fully present where you are. You do not have to go somewhere else to find it. His lyrics have made this point several times, perhaps most notably in Trying To Get to Heaven. I shall return to that.

The insight is so simple that it almost isn’t an insight, but something that just is, the way life itself just is. Life is banal in this sense. Thinking it over, everybody knows that if you are alive, all of life and all its possibilities and energies are always fully and totally present exactly where you are. But we don’t always live like that. Ok, we never do. We are always on the way somewhere else. This is what Dylan’s lyrics draw attention to.

With philosophical-metaphorical precision Bob Dylan marks out the areas of existence that constitutes the good life, a rich living beyond materialistic needs and efforts. It can be hard to imagine for the listener who does not usually venture into the deeper literary layers and psychological strata of Dylan’s imagery. And we don’t often ponder upon what life itself is, as a substance or essence. Dylan often does, as when he evokes cabalistic imagery in “She Belongs To Me”, or when he speaks about “the world” in “False Prophet,” a reading of which was in Dylanology No. 3

In this apparently lighthearted little song, the author maps out the existence we all share. He does so by alluding to a universal condition (Verse 1), the daily buzz of distraction from the real life (Verse 2), living a life rooted and sociable, which is necessary to attain “the good life” (Verse 3), and finally to the will, determination and energy that drives it all (Verse 4). I will look into the lyrics in detail:

Clouds so swift

Rain won’t lift

Gate won’t close

Railings froze

Get your mind off wintertime

You ain’t goin’ nowhere (verse 1)

What sounds like a beautiful, singular landscape description turns out to be something different. None of the three types of weather occurs together. When the clouds are swift, it usually doesn't rain. Swift clouds have open, blue skies. There might be scattered showers, but this is not the kind of rain that “won't lift”. That would be a heavy rain.

The next lines are incommensurable with this. For reasons unknown, the gate to whatever it is won't close – but clearly the railings do not freeze in that kind of rainy weather, whether it has scattered showers or heavy rain.

It seems like all seasons are potentially present at the same time. The wintertime of the last lines of the verse is the only season mentioned. It is the time where either nothing happens, because everything is still and nature is sleeping – or you go somewhere else, where it is warm and nice. But don’t go anywhere, the verse concludes. The refrain is almost like a painting of Chagall:

Whoo-ee! Ride me high

Tomorrow’s the day

My bride’s gonna come

Oh, oh, are we gonna fly

Down in the easy chair!

An Evocation of hope

The refrain is an evocation of hope: Hope for the future (“tomorrow’s the day”), hope for the joy and fulfillment of love and marriage (“my bride’s gonna come”), and the hope that in a bright future like that, life is more easy going. This is where Chagall comes in – the lovers fly through life as in a spiritual dance, to land in the easy chair, where they most likely continue flying, spiritually or bodily.

The image with the bride is larger than this. In religious thought, the holy matrimony, the hieros gamos, is common practice, providing ultimate, existential hope – like in Christianity where the church is called “the bride of Christ” (John 3:29, Mark 2:19 and elsewhere). Dylan uses the metaphor of the hieros gamos in the title of the single from around Shot of Love, The Groom’s Still Waiting At The Altar.

In this sense the refrain is what adds meaning to the essence of the first verse. All of life is present where you are at all times, like all the seasons the verse alludes to, but only if you move forward in time carrying hope, love.

Life's unavoidable practicalities

The second verse departs from landscape description and makes its point about existence through some of life’s unavoidable practicalities:

I don’t care

How many letters they sent

Morning came and morning went

In the late 60s when this song was written, there was no email, telefax or social media, but there certainly were letters and telephone. Just as today you spend your whole life communicating, in this case receiving, reading, and answering letters and telephone calls with ideas and plans, suggestions and initiatives.

The narrator of the song doesn’t care about this. Why? It all takes place somewhere else – and “You Ain’t Going Nowhere”, remember! Everything is right here. But only if you, too, are present. Morning came and morning went – and what did you get out of it? You can either enjoy a new day dawning or you can let it pass without having noticed anything but unimportant messages from somewhere else. The verse continues:

Pick up your money

And pack up your tent

You ain’t goin’ nowhere

The place where you are – and from which you’re not going anywhere – is not a place where you need money or a fleeting place to crash (the tent). As the refrain says, in this place you rest firmly in the easy chair with hope and love. This is truly all one needs.

Maybe it is not an easy chair, in the sense that you sit there comfortably and watch tv. Maybe it is a metaphor for the vantage point from where you contemplate life in hope, love and spirituality. And when you do, You Ain’t Going Nowhere. You are fully here. Maybe it is not a place at all – it is a form of consciousness.

The song continues with the third verse:

Buy me a flute

And a gun that shoots

Tailgates and substitutes

Strap yourself

To the tree with roots

You ain’t goin’ nowhere

We began with landscape, weather, and seasons, something basic that everybody is subject to, and we continued with practicalities like money and communication that tend to distract you from your focus on the here and now. The last metaphor in the third verse firmly underlines this. When you are strapped to a tree with roots you definitely aren’t going anywhere either. To be firmly rooted is an ancient biblical metaphor for the good life (Cf. Psalm 1:3). So if you are so tightly connected to life itself in its most organic and metaphysical form, why would you need these four gadgets: A flute, a loaded and working gun, tailgates and substitutes?

Well, life is not only about resting firmly under universal conditions and strengthening your focus on the now, it is also about interaction with other people. Without interaction you can be as spiritual, as loving and as hoping you want – there is no real living.

The four metaphors (flute, gun, tailgates, substitutes) are in fact two pairs of media for social interaction with opposite properties, both necessary.

The flute is an instrument with which you make yourself heard over a long distance. But this is also something by which you come into contact with life itself exactly where its spiritual and physical dimensions meet each other. What do you use to make yourself known in the surroundings via a flute? You use the wind. The same substance with which you breathe and live.

With the gun you also come in contact with life at a point where the physical and spiritual dimensions melt together – but in the negative sense, namely through death, when they both disappear. So the flute and the gun are signifiers of basic social relations in the positive and in the negative way. In the constructive and the destructive way, both of which are genuine attributes of life itself, life in which everything grow and die.

Where the flute and the gun so to speak are pointed outwards towards the world, tailgates and substitutes are signifiers of social relation turned comparatively inwards (although now it gets very surrealistic): The tailgate is, as it says, something that watches your back – something that makes sure that you can remain alone and by yourself if you need to and if you want to. The substitute has the same effect. It's that which makes you able to go under the radar and hide yourself.

To truly live you need to be social (flute/gun) and you need to be able to be yourself (tailgate/substitues).

The visionary poetical instinct

So we have the universal conditions around our dwelling (verse 1), the distractions from the moment and the fullness of life (Verse 2) and the remedies for real life in a social sense (Verse 3). All wound up by the refrain expressing that which sets everything in motion, hope and love.

I am not proposing that Bob Dylan thought of all these connections as he wrote the song, it is probably penned down over a period of 15 minutes. But what we do know is that he has such a visionary and vibrant poetical instinct that metaphorical images that present existential connections like this are to be found all over his work. I can point to some of the songs that we have read through in the earlier editions of Dylanology, like “Forever Young” and “Most Of The Time” and the re-reading of the album Desire, showing a conscious approach to all levels of metaphors and images in Dylan’s writing.

But now, all of a sudden, comes riding none other than Genghis Khan. What could the fourth verse possibly symbolize in this context? Genghis Khan! Who was he even? A brute, a tyrant, a simple warrior from the Middle Ages?

Genghis Khan

He could not keep

All his kings

Supplied with sleep

We’ll climb that hill

no matter how steep

When we get up to it

What would complete a cluster of existential metaphors around life’s universal condition (Verse 1), about focusing on the here and now (Verse 2), about being rooted in life and (thereby) attaining sociability (Verse 3)? The energy that all this contains, lets loose, and consumes. That is what Verse 4 surrealistically sketches.

Genghis Khan is the individual in the history of the world who rode the furthest with an army. From Mongolia to the gates of Vienna. For a human outpouring of energy, vitality, and lust of life, you could find a more adequate image. But how was it in practice – could he supply his men with food, weapon and what else is needed? No problem! But he couldn’t supply them with rest – there was so much to see, so much to conquer, so much energy in there, so much to achieve by this monumental act that there was no time or rather no way to sleep.

The second image of Verse 4 has nothing to do with the Genghis Khan-image if it is not about the most demanding use of energy and inner power and determination:

We’ll climb that hill

no matter how steep

When we get up to it

In relation to what the rest of the verses have circled around, Verse 4 says: You can do anything that you want, just as long as you stay in tune with life itself. And the song says: Life is always fully present exactly where you are – the rest is a waste of time and an illusion.

It is all there

Now if you were to choose one single Bob Dylan-quote some would choose “You don't need a weatherman to see where the wind blows” and others might choose “To live outside the law you have to be honest,” although this is a cabalistic expression and not something about gangsters.

For a long time I would have chosen “I was so much older then, I am younger than that now,” the refrain of “My Back Pages”, stating a point not so far from what we have been talking about here. Lately the line from “Trying To Get To Heaven” that Bob Dylan on his home page has moved to the last verse, but that in the original recording occurs in the third verse:

When you think you lost everything

you find out you can always lose a little more.

This line says exactly the same as “You Ain’t Going Nowhere, it sums up the whole of existence in an elegant phrase of negative dialectics. It seems to be one of those bitter lines that says, “there's always more evil that's going to come at you.” But it is the opposite. It is a line full of hope and life. It says that life is always present in it fullness where you are: You may have lost everything, but because you're still alive you still have everything to loose. That also implies that you can still have everything. You Ain’t Going Nowhere. There is no need to.