How Does Dylan Write His Songs? (Dylanology 28, Part 1)

Is it possible to extract song-writing lessons from the greatest song-writer of all times?

I was asked by one of the subscribers to Dylanology (and this is a reminder to you all that I welcome questions):

How does Dylan writes his songs? Dylan was self-taught – and he couldn’t google what I–V–vi–IV is. How does he come up with chords to his songs, besides learning from his musical influences and reflecting it in his own music? How does he write his melodies? When he says that he already hears the music he wants when he writes the lyrics, how does that work, concretely?

These are excellent questions – and huge. I will break my answer down into three main issues: (a) the general harmonic language of pop song, particularly Dylan’s version of pop song; (b) the specific genres and styles that Dylan relates most directly to; (c) and Dylan’s own particular idiosyncracies, including a full-scale masterclass in songwriting by the man himself.

Behind the question also lies the subscriber’s wish to write his own songs and to learn from Dylan’s example. I will therefore formulate my answer with a side-glance to these more practical issue of how we can learn from Dylan in our own songwriting.

Chords and Songs

But let us start with the basics: chords and songs. Most people who have ever picked up a guitar know that one cannot just play any chords for a song, because chords belong together in “families” around the main key of the song.

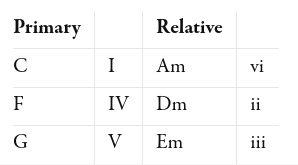

The steps of the scale are often designated by Roman numerals. In a major scale, the chords on the first, fourth and fifth steps (I–IV–V) are major chords, and these are also the main chords in a given key – the “three-chord-song” chords.

In a song in C major, then, these chords are C, F, and G.

The chords on the second, third and sixth steps (ii–iii–vi) are minor chords. In C major, these are Dm, Em, and Am. Each of these minor chords is closely related to one of the major chords, so that I–vi (C–Am), IV–ii (F–Dm), and V–iii (G–Em) form their own little units, where one may sometimes be replaced by the other.

A common way to visualize this is through the “Circle of fifths”, where all the twelve keys are arranged in a circle, where V is found clockwise and IV counterclockwise to the main key:

LESSON 1

Dylan mostly sticks to the six main chords.

So the first answer to the question

how to pick chords for a song the Dylan way, is to

Keep It Simple, Stupid (KISS).

Example 1 – The Simple Song: Blowin’ in the Wind

Take “Blowin’ in the Wind” as an example: nothing but I, IV, and V chords throughout:

Compare Dylan’s own version to virtually all covers of the song: from Peter Paul and Mary to the Bee Gees, they are all genetically unable to resist the temptation to spice up the simple chord skeleton, e.g. with:

and virtually everyone but Dylan sings the end like this:

They just can’t help it.

Dylan can.

Not only can he; it may be so that in the original Freewheelin’ version, which I have used as an example here, the “How many …?” lines are played I–IV–V–I, but in just about every live rendition since then, the V has been omitted, so that both the question and the answer lines, except the crucial “sleeps in the sand” line, are played I–IV–I:

That’s restraint!

Despite their completely unbridled lack of restraint, I still recommend listening to Stevie Wonder’s and Glen Campbell’s live version from 1969, especially the end:

Not Too Simple, Stupid!

But where the first concrete lesson is KISS, the second is:

LESSON 2

A little bit of variety

and unpredictability

amid all the simplicity

is a good thing.

In Dylan’s version, the three “How many …?” questions are all sung to the same chord sequence:

I–IV–V–I.

The first of the “before …” lines stays in the same mood, even shortened to

I–IV–I.

But this restraint makes the shift to

I–IV–V

for the second “before …” line all the more fresh (I will abstain from hyperbole and say “shocking”).

And what’s more: these two “before …”s in fact establish a simple pattern: first something relatively boring (here: I–IV–I), then something more exciting (I–IV–V!). When the third answer (“Before they’re forever banned”) returns to I–IV–I again, we are conditioned through the pattern to expect something even more exciting to be about to happen in the chorus.

And does it?

Well, if one was expecting exciting, jazzy, novelty chords, the answer is: no. But in the last two lines, all the regularity that has been established so far – where every line begins I–IV and continues with very small gestures – is turned on its head. In the penultimate line, we have a complete reversal of the roles of the three chords: here, it’s the IV chord that sets things in motion and to which the phrase returns:

And although the very last part (“… is blowin’ in the wind, / the answer is blowin’ in the wind.”) could be seen as a return to the I–IV–V–I pattern again, it is so in an irregular way: the IV step is twice as long as before, and ends one line and begins the next:

LESSON 3

There should be a sense of direction

within the verse as a whole

– a large-scale structure.

So the large-scale structure in this case could be described: The first phrase barely strays from the I chord; the second takes the I–IV gesture at “Before …” as an excuse to land on V instead. The static character of the verse as a whole is preparation for the more dynamic refrain, where IV and V are finally fulfilling their function of driving harmonic motion and narrative.

A side note: The refrain of “Blowin’ in the Wind” has the exact same harmonic progression as the beginning of “Mr Tambourine Man”:

In a previous analysis, I’ve called “Mr Tambourine Man” a carnival in song, because “everything’s a little upside down”. This is precisely what I was referring to back then, and even here.

Example 2 – Testing the Limits: Don’t Think Twice

In the other end of Dylan’s “simplicity spectrum”, we find “Don’t Think Twice”. It is by no means a harmonically advanced song, but in Dylan’s book, it is.

The first thing we may note is that even though this song is very different from “Blowin’ in the Wind”, the two songs actually share the same large-scale structure: a first phrase that returns securely to I, a second that lands on V, and a last section (which in this case takes up the rest of the verse) which is much more dynamic and eventful, before the whole thing is rounded off with a V–I ending:

Secondly, we may note that there are a few more different chords here. We have the minor vi chord that all the other artists wanted to put into “Blowin’ in the Wind” – and we have a II chord.

This may seem like a trivial addition, but it is actually quite significant. In the basic table of the chords in a key, the second step is supposed to be a minor chord, but here we have the major II chord instead. This means that Dylan has broken his own rule-of-thumb #1: to always stay in the key.

When one leaves the key like this, it is almost always for one particular purpose: to add tension, to create longer lines of resolution, through a chain of dominants or V-relations. For reasons I have explained in other posts, V is the quintessential tension creator, and its resolution to I is what every melodic line wants. Most songs, including the two examples so far, end with such a V–I resolution.

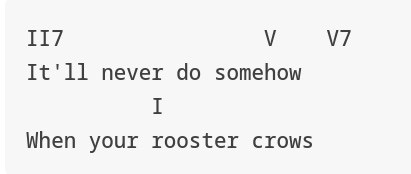

The importance of the V–I relation is the explanation of what the major II chord is doing here: it’s because II is to V what V is to I. So in the central phrase –

– the II chord is not just simply the major version of the expected ii chord. In fact, it has nothing to do with ii whatsoever. The two chords share name and number, but II is an immigrant – from the key of V. What it does here is prepare the V chord, to prolong the line and keep us on our toes just a little longer, before we finally land on I again.

Seventh Cousin Looking In

The second cousin of the dominant/V–I relation is the seventh chord, which is also abundant in this song. What the added seventh does is to heighten the tension and thus strengthen the pull between V and I. That is why the II chord also has the added 7, and why the V chord goes to a V7 chord before the tension is finally released.

And this is also why that same trick is repeated once I has been reached (on “rooster”): when the seventh is added to any chord, it becomes a “temporary V” to the next chord, and this also goes for the I chord, even though its function is to be the stable end-point of any musical narrative. Here, however, it is forcibly transformed to the tension-creator, making the IV chord that follows the temporary goal of the progression.

That means that we can re-illustrate the entire phrase in the middle of the song as follows:

Each chord is a preparation for the next, in an unbroken chain of V–I relations.

The Power Drill Untouched

This way of creating tension and direction through V–I relations and seventh chords is actually the most powerful tool that has been developed in the history of western music. It has been used to tremendous effect by the great composers, to create, control and prolong musical narratives through purely musical means. It provides storytelling without words.

But it is a tool that Dylan has actually been reluctant to use. This may sound strange – why not use the power-drill when there is one in the tool-box? – but it makes perfect sense. The notion of “storytelling without words” has never appealed to Dylan. He wants to control the tension and the flow and the storytelling in the song through his voice and his words.

In that sense, Dylan is not a musical songwriter: he will never let the purely musical means take over. Which is also why the kind of harmonic subtlety that is makes up «Don’t Think Twice» is actually an anomaly in Dylan’s style, and the song itself is an outlier in his catalogue. It could be regarded as a genre piece, a nod to Jessie Fuller and his “San Francisco Bay Blues” or “You’re No Good”, which Dylan had recorded for his first album.

Dylan’s reluctance towards harmonic complexity can also be observed the other way around: when once in a while he does venture outside of the regular chords of his favoured styles, it frequently sounds a little strange. In the Garden is perhaps the most clear-cut example.

LESSON 4

The lesson on this point is double-edged:

if you want to follow Dylan’s example,

use deviations from the main key sparingly

and with great caution.

But: you should also know why you are placing those restraints on yourself:

to give your voice and your words optimal conditions.

If you create a void, using harmonic restraint,

and you don’t fill that void with expressive singing and great lyrics,

you might as well have added as much harmonic spice as you can in the first place.

Dylan’s simplicity is there for a reason.

Example 3 – The Minor Song: All Along the Watchtower

Minor keys tend to work differently than major keys. The chords in All Along the Watchtower, for example, are (transposed to Am): Am–G–F–G–Am etc. forever.

There are two ways to explain how these chords belong together.

One would be to go back to the table of relationships between the main chords of a key. I pointed out in the beginning that there is a close relationship between Am and C. In some circumstances they are exchangeable, because they fulfill more or less the same function.

If we were to replace Am with C in this song, the three chords we are left with would be C, F and G – exactly the standard three chords, I–IV–V.

This is not to say that one can simply do so, always. In the case of the Watchtower, the swap doesn’t really work. However, it is an example of one of those things that one may play around with in one’s own songwriting, as the next rule in the book:

LESSON 5

Knowing not only which chords belong to a certain key,

but also which functions those chords fulfill in that key,

is a good starting point for improvisation and experimentation,

and a necessary step on the path

from memorizing a lot of chords

to understanding the music that they make.

But as I said, the swap doesn’t work in this case. The reason, simply put, is that such a swap works only if G functions as the first step in a V–I progression, in which case the I function can be fulfilled by vi (Am) instead. That is not the case here. There is no V–I relationship in the Watchtower.

Therefore, the other explanation is more plausible: to look for the “narrative” not in V–I relations, but in the contrast between different “tone fields”.

A minor consists of the tones a–c–e, and F major of f–a–c. That is a fairly close match: two of three tones are the same (a and c).

We may also note that the full tone field of these two chords, f–a–c–e, doesn’t have a single tone in common with the third chord of the song, G major, with the tones g–b–d.

Thus, the whole song can be heard as a constant alternation between these two contrasting areas, as a constantly spinning motor. That one of the areas, the Am/F cluster, comes in two different varieties, just adds to the dynamism of the alternation.

These two models – V–I relations as tension generators on the one hand and contrasting tone areas on the other – represent two different kinds of music: tonal and modal. There is quite a lot of confusion and misunderstanding about especially modal music: what does it mean? What is so special about the Dorian or the Mixolydian scales?

For a slightly longer discussion of the modes, I refer to the first of my “Tangled Up in Blue” posts.

Here, I will limit the discussion to mention that in Dylan’s songs, the modal side is found mostly in the minor key songs, especially the more strongly folk oriented songs. Think of “Masters of War”, “Hollis Brown”, and all those wonderful, minor-key songs in drop D tuning. They all alternate between Dm and C, in a way very similar to the alternation between Am/F and G in “All Along the Watchtower”.

In analogy, it would have been possible to use the “Watchtower” kind of alternation also in “Masters of War”:

It is not exactly the same song, but the alternation between two tone areas is the same.

That’s basically all there is to “Masters of War”. And so it ends:

It would have been possible to play the end of the verse in «Masters of War» this way:

In other words: as a V–I song. But that would change the character of the song completely.

LESSON 6

Be aware of the difference between

tonal V–I relations and

modal tone field contrasts.

Play around with them

– turn «Masters of War» into a tonal song if you wish –

and notice what happens.

That’s it for this issue. In the next issue, I will discuss Dylan’s use of form and his way of creating melodies.

But since this is about Bob Dylan, a last lesson is required, after all:

LESSON 7–99

Disregard any talk about lessons or rules.

Don’t let anyone tell you how to play

or how to write your songs.

The minute you have to think about your music,

you’ve already lost.