How Does Dylan Write His Songs? Melodies from Words (Dylanology 28, part 3)

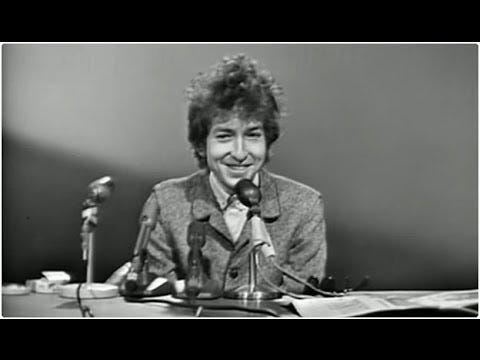

A closer look at some remarks from the San Francisco press conference in 1965

One of the most intriguing aspects of songwriting is the relationship between lyrics and melody. There are two main questions here: What comes first – the melody or the words? and: Is there a determined relationship between them? Can any melody go with any set of lyrics, or do certain lyrics call for some specific tune?

This topic comes up during the legendary San Francisco press conference on 3 December 1965. It was also part of the reader question that prompted this mini-series of posts about how Dylan writes his songs:

How does he write his melodies? When he says that he already hears the music he wants when he writes the lyrics, how does that work, concretely? (thanks to Brayden Gordon for the question, and also for referring me to this exchange in the press conference).

The KQED Press Conference

The press conference itself is a peculiar item in Dylan’s history. One thing is that is is Dylan’s only televised press conference ever. It is also a quite strange thing: it was held at the educational TV station KQED. The journalists present range from professional TV news crews from the local and national press, to editors of local high school papers, as well as Dylan’s friends such as Allen Ginsberg and Ralph Gleason (who arranged the conference).

The huge range of journalists involved is also reflected in the range of the questions that are asked. The press conferences begins with a very serious young man who has given much thought to the deeper philosophy of the cover image of Highway 61 Revisited.

Dylan hasn’t.

Then comes the iconic song-and-dance-man remark:

– Do you think of yourself primarily as a singer or a poet?

– Oh, I think of myself more as a song and dance man, y’know.

… and the equally iconic quip about mathematical music:

What would you call your music?

I like to think of it more in terms of vision music – it’s mathematical music.

Words or Music First?

These initial, mostly wacky one-liners are directly followed by the first really interesting interchange, at least for our purposes here:

– Would you say that the words were more important than the music?

– The words are just as important as the music. There would be no music without the words.

– Which do you do first, ordinarily?

– The words.

A little later, someone follows up this line of thought:

– Bob, you said you always do your words first and you think of it as music. When you do the words can you hear it?

– Can I hear the …?

– Can you sort of hear what music you want when you do your words?

– Yes. Oh, yes.

He then goes on to elaborate – quite confusingly – about how different instruments influence how this relationship works out in practice:

– Do you hear any music before you have words? Do you have any songs that you don’t have words to yet?

– Ummm … sometimes, on very general instruments. Not on the guitar though. Maybe on something like the harpsichord or the harmonica or autoharp, I might hear some kind of melody or tune which I would know the words to put to. Not with the guitar, though. The guitar is too hard an instrument. I don’t really hear many melodies based on the guitar.

An Exegesis

These remarks are given one by one and in a quite humourous mood, so one should necessarily expect a deeper meaning behind them. However, that does not mean that they are taken out of thin air, nor that they are just empty quips. Some of the themes appear again and again in Dylan’s interviews, and although the setting is usually the same – Dylan pulling some poor interviewer’s leg – it would be unwise to simply assume that just because there may not be an entire iceberg of consistent musical philosophy hiding underneath their surface, there isn’t a serious idea behind them at all.

Furthermore, Dylan does actually try to give serious answers to many of these questions.

The Burling interview

The perfect illustration of both these points is in fact the interview with Klas Burling from 1966. By the end of the 1966 tour, Dylan had perfected his cat-and-mouse game with journalists even further, and the poor Swedish victim had the misfortune of meeting a jet-lagged Dylan in a lousy mood, who had also “taken some pills”.

Dylan is ruthless. Burling starts out by asking about protest song and going electric, and Dylan gives it all he has, describing one of his newer songs (which he refers to as “Rainy Day Women”, but which from his description sounds more like “Ballad of a Thin Man”):

It’s sort of a North Mexican kind of a thing, uh, very protesty. Very very protesty. And, uh, one of the protestiest of all things I ever protested against in my protest years.

Then comes the “I happen to be a Swede myself” line, and the “mathematical music” theme again, and the poor Burling is hanging by the ropes.

But then, the miracle happens: Burling asks about playing with a group, and this for some reason prompts Dylan to breaks out into a long, serious and quite interesting monologue where he presents the history of popular music in the USA vs. England, and the position of the Beatles in all this:

There is no mockery, no self-conscious image grooming, no complaints, no condescension. Just an eager, committed Dylan talking about something that matters to him.

Towards the end of the clip, Dylan defines rock ’n’ roll as “just a substitute for sex” and reverts to the “mathematical music” theme. The moment is gone. But it was there.

In other words: when Dylan gets on some track that interests him, he is more than willing to share his thoughts in a serious way. The tip of the iceberg is never far away. That’s the goal of this little exegesis: to treat the off-the-cuff remarks as tips of icebergs and try to squeeze something serious out of them.

The Musico-Aesthetic Iceberg

A first observation is that already in these first few minutes of the conference, Dylan touches upon several different perspectives on music:

the “song-and-dance man” line rests on an idea that music is just entertainment

when he talks about “vision music, mathematical music”, it rather implies that music has a structural, hidden, perhaps even secret layer

His answers to the various questions about the relationship between music and text revolve around the age-old issue whether music is subordinate, equal, or superior to words.

And the line of thought that he goes into about how musical instruments influence the resulting melodieshas to do not only with the relationship between technology (in a broad sense) and music, but more importantly with whether song is directly tied to the voice (and hence to words) or is an independent mode of expression.

These are all huge questions. Dylan of course doesn’t answer them in his short one-liners, but there seems to be a semi-conscious and semi-worked-out idea behind them.

This is perhaps most clearly apparent from the way he almost consistently misunderstands the questions, or at least answers some other question than the interviewer had in mind.

“Who’s On Top?”

The first interaction is a good example. The interviewer asks: “Would you say that the words were more important than the music?”, and it is as if Dylan goes defensive in two directions at once. He hears the question – probably correctly – as one where the interviewer expects a positive answer: “yes, I’m the voice of a generation – of course the words are number one, and the music is just a carrier of my deep, mystical-political insights.” Something like that.

He does not want to confirm that stereotype, so he turns the question on its head and answers “The words are just as important as the music”, thereby indirectly implying that the music is the most important element, at least that one might have that idea (although I doubt that anyone in 1965 would have thought so about Dylan’s songs), but that the words are in fact – against all expectations – just as important.

But the follow-up actually reveals Dylan’s real stance: “There would be no music without the words.” In other words: music has no existence or legitimation of its own; it is actually there simply as a carrier of words.

He then reaffirms this bias by confirming that he does indeed write the words first.

“Does the Music Come with the Words?”

This starts a chain of quite interesting misunderstandings. When Dylan answers: “There would be no music without the words,” he clearly means that what he does is write songs, and without the words there would be nothing to attach a melody to. But the next interviewer takes this to mean that “you always do your words first and you think of it as music”, i.e. that the melodies somehow are inherent in the lyrics.

This is not at all what Dylan meant, but he actually goes on to confirm it, although what he has in mind with his answer is rather a rephrased version of the question: “Can you hear what music you want when you do your words?”, which is a much broader question: in Dylan’s mind the question is probably not whether specific musical details spring directly from the words, but rather translates to: “Do you have a general idea of genre, tempo, style, etc. when you write a set of lyrics?”

That is what he confirms when this line of thought ends with the question “Can you sort of hear what music you want when you do your words?” “Yes. Oh, yes.”

“What comes first?”

The next follow-up doesn’t make things any clearer. The interviewer asks: “Do you hear any music before you have words? Do you have any songs that you don’t have words to yet?”

What she means is clearly: “Could the process go the other way around – that you write the music first and then the words?” Dylan’s answer is to a completely different question: about how the melodies he writes are conditioned by the instrument he is playing them on:

– Do you have any songs that you don’t have words to yet?

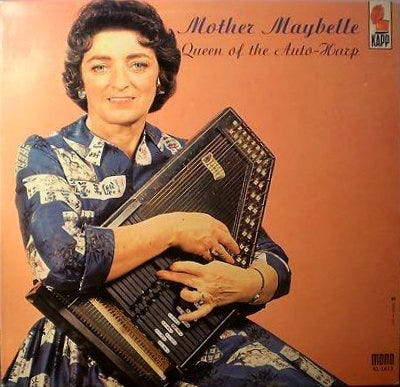

– Ummm … sometimes, on very general instruments. Not on the guitar though. Maybe on something like the harpsichord or the harmonica or autoharp, I might hear some kind of melody or tune which I would know the words to put to. Not with the guitar, though. The guitar is too hard an instrument. I don’t really hear many melodies based on the guitar.

If taken literally, the answer he gives is balderdash. The list of instruments, for example: to my knowledge, Dylan has never played the harpsichord, the Baroque keyboard instrument (and besides, it is in any case just an ordinary keyboard instrument with a plucky sound, so it is hard to see how writing on a harpsichord would be any different from writing on a piano);

the autoharp is a completely different instrument, with completely different preconditions when it comes to songwriting, since it is a purely chord-producing instrument with no ability to play a melody line at all;

and the way Dylan uses the harmonica, it is not in any way a song-writing tool.

So I’m convinced that the list of instruments is bogus, and that the thing about the guitar being too hard an instrument is – at best – not quite thought through. But the general idea: that some instruments create associations to melodies more easily than others, may be worth digging into a bit more.

There may for example be a genre connection, in that the autoharp, for example, is more readily associated with certain genres, and that these genres carry with them a distinct melodic repertory.

There may be a basis in the sound characteristics of the various instruments, where – again – the autoharp produces full, ringing chords that are fixed and static, which may inspire a certain kind of melodic improvisation, whereas the strings harpsichord have a very short sound, which may lead to a different kind of tunes.

Different Kinds of Instruments and Musicians

The remarks about the guitar are intriguing. Why would the guitar be “too hard an instrument”? What are those “very general instruments”, and how does the guitar differ from them?

To answer this, I would like to take a brief detour.

There’s one scene in the BBC Classic Albums documentary about the making of The Band’s first two albums, that has always been dear to me. It’s Garth, of course. Garth Hudson is sitting in a dense forest of keyboards. All that can be seen of him is the top of his baseball cap, and his fingers, which are all over the keyboards. He is meandering his way through a weird, complex modulation, then halts momentarily, grunts: «how to get out of this one? quick! quick!» before his fingers find their way, on their own accord, out of the wilderness and back to some cadence, before they immediately move on into the next harmonic adventure.

That’s exactly the kind of musician Dylan is not – especially when he is on the guitar.

On the piano, the notes are laid out logically. Garth’s fingers can find their way on their own.

The guitar is very different in this respect, and especially the way Dylan plays it. It is much more difficult to play individual melodies on a guitar, and especially several melodies at the same time the way Garth does. Playing guitar mostly means: playing chords – not melodies.

That may be the distinction Dylan attempts to outline: between general instruments on the one hand – either with a very rudimentary inner logic, such as the autoharp, or with an immediate, visual logic, such as the piano – and the guitar on the other, which is a hard instrument in the sense that playing the guitar to a much greater extent is based on hand-muscle memory rather than musical logic, and so working out a melody on the guitar becomes much harder.

This will become clear in a very concrete way in the next issue, where I will go through Dylan’s own song-writing masterclass. In it, we find Dylan constantly searching for chords that go with what he is trying to do, chords that fit the melodic outline that he has a vague idea of and is trying to grasp, and he does so not by trying out different musical or melodic ideas, but by trying out various chord shape combinations from his repository of muscle-memorized changes. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. Contrast this with Garth, who is toying with three–four different melody lines at the same time, which happen to produce pleasing chords along the way.

Words + Music = Phrasing

The various discussions of the relationship between words and music in the San Francisco press conference may be a mess which does not lead to any firm conclusions – should anyone have expected that.

When I still find it interesting to dive into the scattered remarks, it is because of the underlying topic that he hints at: that he somehow senses a connection from his texts to his melodies.

Even though this connection may not consist of a straight line from words to melody, what remains clear is that Dylan’s lyrics always seem to have been written with vocal delivery in mind.

It is not something Dylan himself mentions in any of the interviews, but in hindsight we can say with confidence: the one huge, natural link between melody and lyrics is phrasing. And that has always been the core element in Dylan’s vocal style.

Very moving sequence of Garth Hudson making his way through chords. Apart from that, I have a very serious problem with Dylanology. The usual path: log-in, connect, read and save to reread offline, is impossible. All the posts I saved are not the full version of what I read. Is there a way to skip Substack, who seems to be the responsible fot this frustrating situation?

I, too, have a very serious problem with Dylanology.

I find myself thinking, whenever I read any of your work on Substack, “does this guy even like Bob Dylan?”

Because if you don’t like Bob Dylan, then I don’t know why you bother to write about him.

I signed up because I thought you were the guy behind Dylan Chords, which was an eye-opener for me and gave me so much pleasure: I can’t thank the person enough who did all that work transcribing all the songs and all the various versions.

But the writing on this Substack sounds like that of a person who is ambivalent about the subject he’s writing about and isn’t really a staunch admirer of the artist’s work and methods.

If you don’t know whether you like Bob Dylan, or dislike him, or have various mixed feelings about him because of whatever reason, over exposure, you’ve delved too deep, you’ve spent too much time, it’s become an obsession, maybe jealousy and resentment have finally reared their ugly heads, I don’t know, but perhaps it’s time to stop writing about Dylan if it is no longer a labor of love.

I get it: Picasso was an asshole, treated women badly, and Hank Williams drank too much and treated women badly, but I don’t care what they did outside of their vocation of creating art, I’m just admiring of the art they created for the world.

I don’t need an academic treatise to enjoy looking at Picasso‘s horny, ink drawings, and I don’t need an academic dissertation when I listen to “Clothesline Saga” or “If Dogs Run Free” by Bob Dylan.

But you know that.

I can’t read too much written about Bob Dylan any more for it brings me down whereas listening to his music can be transformative, enlightening, and takes me out from my staid, normal consciousness. And when I perform one of his songs and fully inhabit it, I am completely transported out of this time and space.

Bob may not long for this world of touring as he’s getting up there a bit in years, but it seems like an entire industry of writers has grown up lately trying to cash in a few bucks by writing about Bob Dylan.

I remember reading about a guy, AJ Weberman, going through Dylan‘s garbage, and I thought that was so pathetic. Most everyone thought the same way on that. But he was merely a harbinger of things to come: people who try to make a living off of an artist’s back.

Are you doing any better than that? Or would you consider setting down the pen for a while or taking an entirely different approach to writing about Bob Dylan?

I’m so sorry that your pieces, for me, never leave me feeling uplifted or transformed or enlightened, and I don’t enjoy reading your writing about Bob Dylan.

I’d like to think Bob’s attitude on this is from an old, old song,

“I’m a rambler and a gambler and my money’s my own, and if you don’t like me you can leave me alone.”

Love that song.

It’s the kind of writing that brings me joy and pleasure.