In Nobel Denial 2: The Committee’s Flawed Motivation (Dylanology 27)

Why Bob Dylan Should Not Have Received the Nobel Prize, part 2

In the previous post, I summarized the bad arguments against Dylan’s Nobel Prize, which go along the lines that (a) he has written some bad poetry (although even the most obvious cases, such as Wiggle Wiggle, are not as clear-cut as they may seem); (b) he is a bad writer – or at least just someone with a guitar who dabbles in the field of literature (although this “argument” is hardly backed up with evidence, other than that he is a mere strummer); and (c) it’s not literature that he’s doing in the first place (since true literature requires solitude and contemplation, not amplifiers and a cheering crowd.

If you haven’t yet, read the previous issue:

Why Dylan Should Not Have Received the Nobel Prize (Dylanology 26)

One sunny spring day in 1997 I was sitting at a café discussing today’s great news item with a friend over a cup of strong coffee and a gigantic cinnamon roll: someone had nominated Bob Dylan for the Nobel Prize in literature. The news was mostly received as a slightly amusing provocation.

If these can be dismissed as faulty reasons why not, it it time to take a look at the positive arguments: the reasons why he did get the prize. I claim that these, too, are seriously flawed, which is my main reason for thinking the Nobel Prize was a bad idea: they show no understanding of what kind of an author Dylan is, and the result is that the award does not become the honour it was meant to be.

“Creating new poetic expressions”

The short – very short – motivation from the Nobel Committee fits, if not on a stamp, then at least on the diploma:

for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.

That’s it.

That’s actually it. That’s all the motivation they cared to give for why they chose to give the greatest award in the literary world to a controversial recipient like Dylan.

The Benevolent Exegesis

Since that is all we get, let’s analyse this, take it apart and twist whatever meaning we can from it. What does it mean, to have “created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition”?

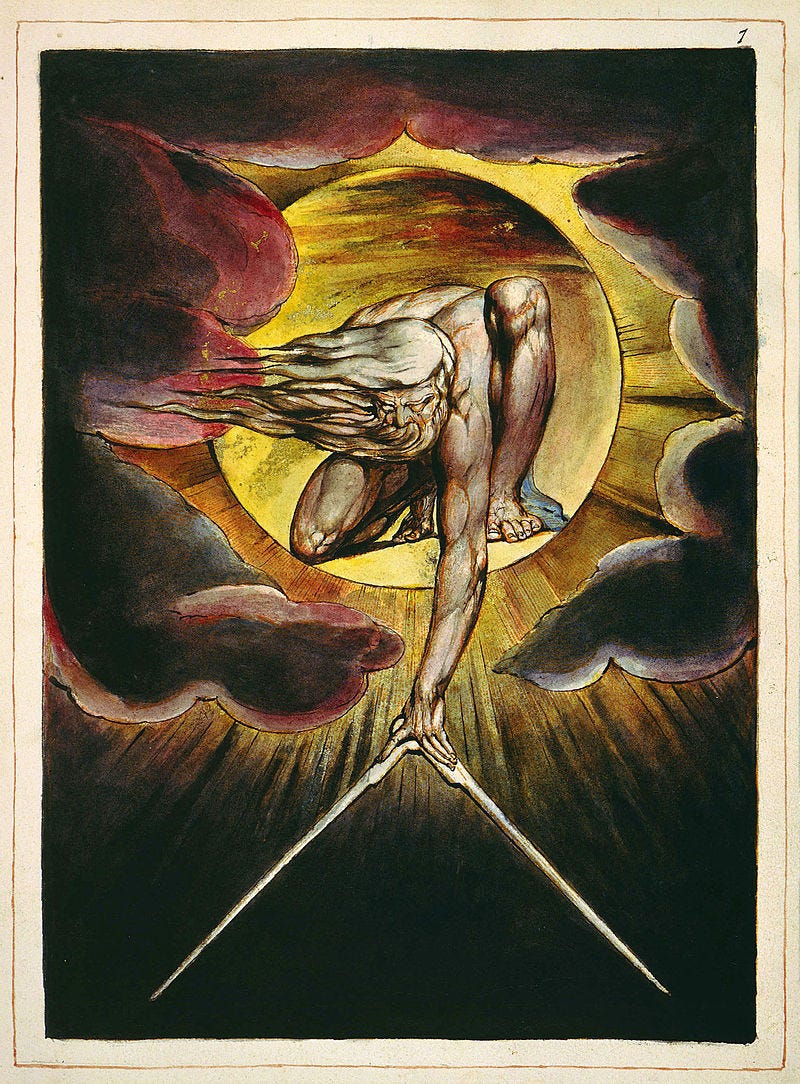

He has created. That’s something. Creating is good – it’s what gods do. In fact, until 1623 the word had never ever been used about any human being, only about God. Creation is God’s exclusive domain. Creativity can’t be taught in Arts-And-Crafts class.

Dylan has created something new. Again, we are close to the world of Mediaeval mysticism and the notion of creatio ex nihilo – creation out of nothing.

And what has he created anew? Poetic expressions. As it happens, poiesis is another concept that lies close to the metier of gods. In the history of music aesthetics, the poetic enters with full force in the Renaissance in an attempt to find a term, alongside theory and practice – a term for that which the great composers do (a term and a concept that was new at the time): not just thinking lofty thoughts, which the dusty theorists did, or doing the skillful things the virtuosic singers could do (praxis). It was clearly felt that composing music was a third kind of thing: it was to fabricate something perfect, shaping, forming, bringing about a work of the highest order. They didn’t dare to take the final step and say: “What God does” – so they used poiesis instead.

And to create new forms of expression goes to the core of the age-old distinction between two ideas of what art and beauty is: between things and thoughts. Is beauty rooted in properties of objects and how matter is arranged in a harmonious and pleasing way, or are we instead concerned with something akin to utterances in a language – the ability of phenomena such as symphonies or paintings to be communicative – to express emotions, ideas, perceptions in a convincing way?

In other words: should art aspire to be beautiful or to be expressive? – that’s the dilemma that sparked heated debate around 1600 when Monteverdi dared to write ugly music to express ugly sentiments. But the same idea can be found way back in antiquity, when Plato refused to include poetry among the arts, because there were no rational rules behind what the poet did; poets are madmen, driven into frenzy by the gods, thereby gaining insights that are beyond the reach of us mortals.

With their formulation, the Nobel Committee could be seen as promoting the value of different and new ways of achieving poetic madness.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dylanology to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.