Murder Most Foul – An American Litany

This text was previously published on my blog, Things Twice. It is now revised and updated with sound examples. It is in many respects the precursor of the R&RW series, which is why I include it here.

It is early 2020. The pandemic shutdown is everywhere. Dylan hasn’t released a self-penned song since 2012 – eight long years ago. The past decade has been strange days indeed, with album upon album of Sinatra-covers, paired with gems from the vaults, bringing the Bootleg Series up to vol. 15.

And then, one late evening in March, a new song materialized, out of the blue – announced on twitter, of all places:

“This is an unreleased song we recorded a while back that you might find interesting. Stay safe, stay observant and may God be with you”.

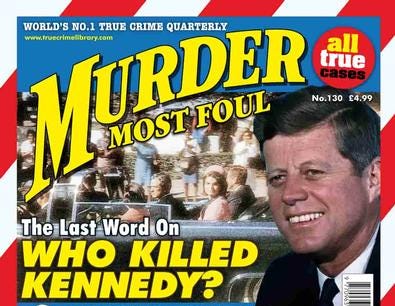

The song was Murder Most Foul – seventeen monotonous, monumental minutes of recitative about the killing of Kennedy, Dylan’s longest song ever.

It turned out to be the tip of an iceberg: two more songs followed, False Prophet and I Contain Multitudes, and then, eventually, the full album, Rough and Rowdy Ways.

Murder Most Foul is not the best song on the album by far, but it holds some of the keys to it.

First Impression: Perfected Nothingness

On first hearing, it sounds like an endless rattling of more or less loosely coherent images and motifs associated with the murder of Kennedy, but also with the USA since the 60s, especially the musical side to the country’s history – the Great American Songbook that Dylan has loved and cultivated, which brought him the Nobel Prize in the end.

The impression of a formless, quietly flowing flood of visual and textual images is being underpinned by the music. The melody – if that’s indeed the right name for it – is a steadfast recitation on one single tone, alternating at times with new recitatives one note higher.

It is as if the fight against musical development that Dylan has been pursuing over the past couple of decades has finally come to an end: finally, nothing happens!

Verses Great and Small

And yet: The song seems formless and tedious, but at the same time it is strictly structured.

The top level is marked by the title of the song, which occurs as a textual refrain, in total four times during the seventeen minutes the song lasts. Each time it is followed by a brief instrumental interlude. The interlude is heard one extra time, without the refrain, so the song can be divided into four or five “great verses”.

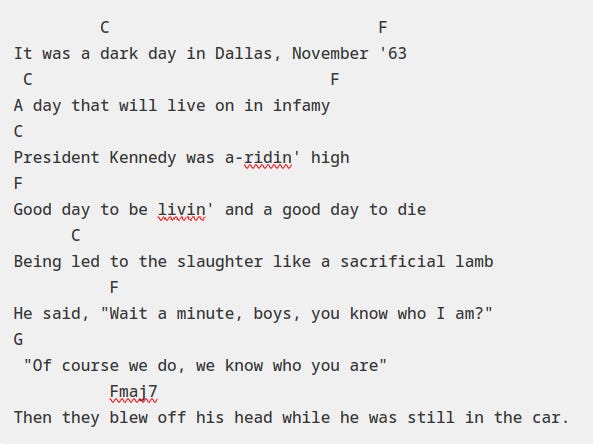

Each “great verse” consists of two to six “small verses”, again of varying length, but following the same structure. The first “small verse” goes:

First an alternation between C (I) and F (IV), repeated a varying number of times from verse to verse, while Dylan and the bass both recite monotonously on C.

Then, as a “climax” of sorts, the chord shifts from F to G and the “skeleton key” of Dylan’s voice rises one tone to D.

The F–G turn can be repeated ad libitum, until the “small verse” ends, with a return to F, and we’re ready for the next round – in this example only once, in other verses twice.

Each “great verse” consists of 2–6 “small verses”, the last of which ends with the refrain “Murder most foul”, some times – but not always – with a return to the keynote C.

That’s it.

A Music Analysis of Three Chords and Two Tones

It may seem trivial and exaggerated to start off with a musical analysis of a “song” that uses two tones and three chords in simple combinations that are repeated perpetually.

But that’s what I intend to do, since the principles that are revealed through this analysis, are central not only to this song, but to the quest that Dylan has been on during the twenty-first century.

1. The chord structure in the “small verses” is closely related to the twelve-bar blues structure. There, too, we start out with an alternation between I and IV and end with the V–IV turn that we find in Murder Most Foul. The pattern is handled more freely here than in most blues songs, but it is clearly recognizable all the same, especially to those familiar with Dylan’s production: the blues goes as a red thread through his entire catalogue of songs.

2. The variability in length is also a known trick with Dylan, from his “talkin’ blues” songs of the sixties, where the V-step, leading up to the punchline, can be stretched for as long as one likes; as well as single lines with a varying number of syllables (not-so-subtly parodied by Tom Lehrer in his Folk Song Army: “The tune don’t have to be clever, / And it don’t matter if you put a coupla extra syllables into a line.”) Murder Most Foul is on a whole other level: there’s a huge difference between adding an extra syllable here and there, and to embark on a quarter of an hour’s formless recitation, without the signposts that a recognizable verse structure might give.

3. “Refrain” today usually means “chorus”: an extra verse with a fixed text that is sung between the regular verses. But in the ballad tradition that Dylan is also part of, going back to the sophisticated courtly songs of the Middle Ages, the refrain was primarily a recurring textual element towards the end of a larger unit of text, not necessarily with its own music or singled out as a separate verse, but structually part of the verse to which it stands. This is a musico-poetic form that Dylan has used just as consistently as the blues, e.g. in The Times They Are a-Changin’. The four refrains, “it’s a murder most foul”, can thus stand as the structural pillars upon which the song rests.

4. The extended refrain structure is a style of writing that Dylan has been working on at least since the turn of the millennium. Its first major appearance was in the song ’Cross the Green Mountain, written for the soundtrack to the movie Gods and Generals (2003) about the American Civil War (once again a freestanding, grand, epic ballad, which is thematically tied to dramatic and violent episodes from American history). There, there is no refrain, just occasional verses with a slightly different chord sequence, interspersed between the regular verses.

Nettie Moore and Workingman’s Blues #2 off Modern Times (2006) have a similar construction, with a sequence of verses followed by a refrain. In these cases, the number of verses is fixed.

Mississippi is related as well, with long verses consisting of shorter units that are repeated, and a contrasting section – this time not as a refrain.

One more thing is worth mentioning about all these songs: the repeated sections, that work as “regular” verses, are not very exciting, harmonically speaking. Some of them have an ascending or descending bass line over more or less static chords, some have some kind of alternation between static chords – almost a standstill, which the “refrain” sometimes breaks, sometimes not.

5. So we may ask: is this really a form? Is it not simply a formula, a loose frame for recitation? And, yes, that indeed seems to be the point: this song structure that Dylan has been working with, is in itself not very exciting – what makes it worth a closer look is what he does with it.

It all has to do with phrasing. It is not controversial to call Dylan the master of phrasing in general – in the sense of shaping a melodic line to a text in a way that uses the sound elements of speech to make the melody seem more immediate, like speech; this is what I’ve elsewhere referred to as “prose singing”.

But on Murder Most Foul he takes this to a new level – literally speaking. It is no longer a matter of aligning the syllables of the text to the musical grid of emphases, but of aligning the lines of text to the large-scale patterns of a chord sequence and a verse structure.

Compare for example some of the G–F passages that end the “small verses”. In the first verse , we find the normal situation: each new chord goes with a full line of text (the soundclip can be heard above):

In the second verse, the F part of the pattern is generally very short, only as a brief pause before the next line hurries in – this is the only part of the song that breaks the calm river-like flow:

Whereas in the third “great verse”, it’s just as much the G part that is short:

And in the long “Play it” final section, the phrase structure more or less collapses at times:

Here, three lines of text are fitted to two G–F sequences (and the first line of the next verse brings the rhyme word “Alcatraz” that goes with “All that Jazz”) .

The Dylan Trick

How much of this that is planned, I would not dare to guess, and perhaps that is precisely the point: the steady sequence of C–F, C–F, G–F, etc. is not even a song structure, it is more like a sounding greenscreen that may or may not serve to emphasise something other than the tune itself, shape the narrative, let other aspects of the vocal delivery come to the fore than those normally associated with a melody; a systematized irregularity, if you like: the phrasing is not entirely loose, but definitely not fixed.

Where I do dare a guess is here: the musicians have not had a detailed score or chord chart in front of them; Dylan has probably not had a clear plan about where to change chords and verse lines before they pressed “record”; and it may not even have been obvious where the verses, small or great, should end. There are places where other dividing lines than those that ended up on the track would seem more logical – the obvious example is the “Jazz / Alcatraz” rhyme above. I imagine Dylan sitting there with a stack of papers in front of him, with a long string of lines on them, with no given verse structure, other than those given by the paired rhyming lines and the occasional refrain – and a group of musicians on their toes to guess where he’s heading and when he’s changing from chord to chord and from section to section (and it is obvious that at times they don’t guess the same thing).

It’s Dylan playing his usual trick: “Let’s mix it all up and see what happens!” That phrase, in some form, has been reported by his musicians ever since the 60s, and it still seems to be his way of working to this day. This can be heard explicitly in the one of the studio outtakes for Tell Ol’ Bill from 2015. In the following sound clip we hear the end of one take, played in the simplistic major key oompa-oompa style that was used for the official release. Then, while one player tunes his guitar and the bass player doodles, Dylan strikes a minor chord on the piano and says, seemingly as if it’s an idea he suddenly came up with: “Maybe we should just change it all, totally. Change the melody, change everything about it. You know, put it in a minor key, I mean, everything!” And as usual, the result is quite rewarding.

The Narratives of a Dead Kennedy

Both the sheer length of the song and the seeming eventlessness makes it difficult to survey the song while listening to it. The refrains are of great help here: if we allow ourselves to assume that the four/five refrains can indeed be used as markers in the long text mass, and that the texts between the refrains are somehow united, where does that lead us?

The first “great verse” sets down the historical framework. The storyteller holds the microphone. The events in Dallas on that fateful day in November 1963 are narrated, with references to conspiracies (“You got unpaid debts, we’ve come to collect … We’ve already got someone here to take your place”), to the mysteries captured on the Zapruder film (“Thousands were watching, no one saw a thing”). The verse is full of historical references, e.g. to the attack on Pearl Harbour (“A day that will live on in infamy”, cited from Roosevelt’s “Infamy” Speech), but also subtle self-references: Kennedy’s line “Wait a minute, boys, you know who I am?”, will be recognized from Dylan’s own song Hurricane, dealing with yet another huge and traumatic issue in American history: racial injustice.

The second “great verse” begins: “Hush little children”, and this sets the tone for the entire verse: the quotation from a childrens’ song continues with holding hands, sliding down the bannister, being ordered to go get your coat, and a series of admonitions that a child might hear, some of which sound like actual commands that could have been shouted in Kennedy’s car but that might also double as general sayings (“try to make it to the triple underpass”), others that sound like general sayings but may be much more concrete (“When you’re down on Deep Ellum, put your money in your shoe”), some that are definitely general statements but get a wider significance in this particular context (“Don’t ask what your country can do for you”).

The narrator has put on a different hat: it is no longer the storyteller speaking, but the tutor, the “wise old owl” who observes the events coolly and communicates to us children what he sees, in short sentences, clichés, commands. There is no condemnation or moral indignation, just observation and orders. “Business is business, it’s a murder most foul”.

The third “great verse” is mindblowing, both metaphorically and literally. We are inside the head of the President while it is being blown to pieces – a unique insider perspective from a dying man, and we witness his surprised hallucinations while he observes his own death, partly as a very close observer (“Ridin’ in the back seat next to my wife, … leaning to the left, I got my head in her lap”), partly as a detatched soul, hovering over the scene, following the events depicted in the Zapruder film closely, before leaving it at 2:38 when the president’s dead and Johnson is sworn in.

The drug references that the verse is full of make complete sense as the blurred haze of a brain about to go out: it starts out with two nods to The Who’s rock opera Tommy, dealing with drug-induced hallucinations (“Tommy, can you hear me”, “Acid Queen”), then continues with brain damages, dizzy Miss Lizzy, and the famous “magic bullet” that has “gone to my head” – this time very concretely.

Play for Us – Pray for Us

Which leads into the the long final sequence of “Play it” lines, formulated as calls to the radio DJ Wolfman Jack.

A lot of effort has been put into deciphering the codes behind the selection and the brief characterizations that each song or cultural item is given in the song, and thereby (re)constructing Dylan’s world view (and his record collection).

In this respect, Murder Most Foul is a textbook example of the literary genre that Dylan himself has created: Bones to the Vultures – flinging around obscure references, secure in the knowledge that someone out there will dig it out some day. (And if you have found a deeply buried bone, it surely proves both that the idea behind it is deep, and that you are, too, since you’ve found it.)

Murder Most Foul is a smorgasbord for the Indiana Joneses of the literary world.

In this case, I will rather go in the opposite direction: disregard completely every single reference and rather see them as a whole – as one huge “great verse” where a seemingly endless row of characters pass before our eyes and ears in a procession. One by one they step into the light before they recede into the multitude again, but the remaining impression is that of the procession itself, not of the individual participant.

The closest parallel I can think of is the litany of saints, the liturgical celebration where all the saints of the church progress, one by one, to let us pray for their intercession before God:

V. Sancte Stéphane.

R. Ora pro nobis.

V. Sancte Ignáti.

R. Ora pro nobis.

V. Sancte Polycárpe.

R. Ora pro nobis.

V. Sancte Iustíne.

R. Ora pro nobis.

V. Sancte Laurénti.

R. Ora pro nobis.

V. Sancte Cypriáne.

R. Ora pro nobis.

V. Sancte Bonitáti.

R. Ora pro nobis.

And so on, indefinitely. “Pray for us!” we sing in the litany. “Play for us!” Dylan says – the effect is the same.

It is not very important who Saint Polycarp and Justin were, or what it is about “Stella by Starlight” that appeals so much to Lady Macbeth. They are all there – they have all made their contribution to making the world a little more bearable, especially when it gets tough, be it because the president has been shot or because the world is sick in one way or the other, or just because one needs something to keep one’s head above water. It is like walking along a bookshelf, reading the titles: one doesn’t even have to have read the books to feel a certain comfort: they are there, standing in line with their contents ready to enthuse us, whether we will ever read them or not.

This is also why the song’s finest moment is its last: when the last member of the procession is the song itself, when the long line of “Play …!” admonitions ends with “Play ‘Murder Most Foul’!”.

This is not hubris or self-aggrandizing on Dylan’s part – on the contrary. He steps into the procession together with all the others. And by doing so, he also makes sure the song lasts forever: every time the Wolfman has worked his way through the playlist, he will have to start all over again. It’s the Great American Songbook version of the eternal heavenly praise of the angels.

There are things I don’t love about Murder Most Foul. While I can live with the wrong key designation of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata (which was written in C sharp minor and not in F sharp), I have more of an issue with the stilted religious language.When the site of the assassination is referred to as “the place where Faith, Hope and Charity died”; when Kennedy is slaughtered “like a sacrificial lamb”; and when Dylan echoes Pilate’s question before Jesus was sent to be crucified: “What is the truth?”, we are way past the religious varnish that a secular litany for the greatest American saint of the twentieth century might call for. It virtually becomes Christ himself who was shot in Dallas on that November day.

But I don’t mind. Just play me “Murder Most Foul” again – just once more.