Rough and Rowdy Ways I: Dylan’s Large-Scale Minimalism (Dylanology 30)

In three posts, I take a closer look at Dylan's latest album, Rough and Rowdy Ways, as a project of large-scale minimalism in the vein of “Cross the Green Mountain”. In this issue, I focus on form.

In the previous issue of Dylanology, I introduced Dylan’s Civil War epic “Cross the Green Mountain” as the grandfather of Rough and Rowdy Ways. I emphasised the carefully crafted uneventfulness; the new attitude towards the main building blocks verse, refrain, and bridge; and the irregular large-scale form of the song as a whole, with blocks of varying length and Great Verses consisting of a varying number of regular verses.

All these features recur in much of the music that Dylan has written during the years since 2003, to such an extent that it may seem like a conscious songwriting strategy as well as an aesthetic project.

This is especially true about Rough & Rowdy Ways, Dylan’s latest record.

The end of the Sinatra Era

When Rough and Rowdy Ways came out in 2020, it was Dylan’s first self-penned song on record in eight years. In the years between, he had immersed himself in the repertory that is most strongly associated with Frank Sinatra, with three single and one triple album as a result. (Shadows In the Night (2015), Fallen Angels (2016), and the triple album Triplicate (2017). I also count the Christmas album Christmas in the Heart fra 2009, which mainly consists of songs taken from Sinatra’s own Chistmas records.)

Then there was the Pandemic, and then, one late evening in March 2020, out of the blue there was a post on Twitter:

This is an unreleased song we recorded a while back that you might find interesting. Stay safe, stay observant and may God be with you.

The song was the monumental “Murder Most Foul” about the Kennedy assassination.

In April and May two more single songs came out (“I Contain Multitudes” and “False Prophet”). There were speculations about the possibility of a full album, and 19 June 2020 it came out: Rough and Rowdy Ways, universally acclaimed as Dylan’s best since 1997, or since 1975, or even since 1966.

The Lahlum Doctrine

During one of Magnus Carlsen’s Chess World Championship games, the Norwegian commentator Hans Olav Lahlum exclaimed: “It is extremely exciting – nothing happens!” That’s the spirit in which Dylan is working on Rough and Rowdy Ways.

More concretely, it’s about self-imposed limitations both harmonically, melodically, and formally.

In his lyrics, Dylan has always been challenging the limits, but formally and musically he has been more moderate – limited, even. He discovered the bridge in the mid-60s, but other than that, he has mostly stuck to fairly simple verse/refrain forms of various kinds.

Also, he has never cared much for harmonic finesse. When he is called a three-chord musician, there is some truth in that (although I have done my best to nuance that picture, both with regard to the simpler songs such as Just Like a Woman and Mr Tambourine Man, and the more complex ones, such as In the Garden (see Dylanology 12) and Black Rider.

He has written some good tunes, but it is not melody per se that has been his main area of distinction.

On Rough and Rowdy Ways it is as if all these tendencies have been turned up yet another level, so that it’s no longer just about a limited use of the available musical means, but about a conscious minimalising.

The term “minimalism” is used to denote certain currents in various forms of art. In the area of music, it is most closely associated with the American composers Philip Glass, Steve Reich, and Terry Riley, among others. When I used the term here, it is in part with reference to some of the techniques developed by those composers – especially a gradual variation of repeated rhythmic patterns – but not necessarily to their aesthetics in general.

Minimalism I: An Exploration of Form in Variation and Repetition

Refrains

The refrain has been a central element in Dylan’s formal language from the very beginning. But a refrain is not one thing. By definition, a refrain is a repeated block of text that is sung to the same music every time. How much is repeated can vary strongly: an entire stanza, a full line, or merely a word or two.

In “Like a Rolling Stone”, a whole stanza is repeated, to music that contrasts with the verses.

In “Blowin’ in the Wind” it’s the entire end of the verse,

and in “Tangled Up in Blue” and “The Times They Are A-Changing” it’s just the last words that are repeated, like a recurring punchline.

On Rough and Rowdy Ways the use of refrains is more complex and varied than ever before.

NO REFRAIN. In one end we find the blues number “False Prophet” which has no refrain at all – slightly surprising, since the refrain is almost a genre feature in Dylan’s blues …

LAST-LINE REFRAIN. … such as in one of the other blues songs on the album, “Crossing the Rubicon”, where each verse ends: “… and I crossed the Rubicon”.

Similar last-line refrains are used in “I Contain Multitudes” and “I’ve Made up My Mind to Give Myself to You”.

FIRST-LINE REFRAIN. A closely related refrain type is found in “Black Rider”, where each verse begins with the title phrase.

PENULTIMATE-LINE REFRAIN. All the remaining songs have refrains as well, but of more unusual kinds. In “Goodbye, Jimmy Reed” it’s the penultimate line that begins with the title phrase, but the line continues with different greetings verse by verse (“Goodbye, Jimmy Reed, godspeed”, “… goodbye, goodnight”, “… goodbye, good luck”, “… goodbye and so long”, “… and everything within ya”), followed by a last line that is new for each verse.

FLOATING REFRAIN. “My Own Version of You” is tricky. The first verse ends with the title phrase, which therefore sounds like a refrain, by genre expectations:

[1] I’ll bring someone to life, is what I wanna do

I’m gonna create my own version of you

But this expectation is broken in verse two:

[2] I’m gon’ make someone a life, someone I’ve never seen

You know what I mean, you know exactly what I mean

Only in verse three it begins to become clear that there is in fact a refrain here, but it’s not the last but the penultimate line:

[3] I’ll bring someone to life, someone for real

Someone who feels the way that I feel

In verse two, the refrain character was concealed through the slight modification of the text (“make someone a life”). But from here on, all the refrains begin with “I’ll bring someone to life”. There is no trace of the title phrase for the rest of the song.

DECEPTIVE REFRAIN. A similar, “floating” refrain is used in “Mother of Muses”. The first verse goes:

Mother of Muses sing for me

Sing of the mountains and the deep dark sea

Sing of the lakes and the nymphs of the forest

Sing your hearts out, all your women of the chorus

Sing of honor and fate and glory be

Mother of Muses sing for me

The first and last line both use the title phrase, and a pattern is created, emphasised by the intermediary “Sing …” lines. So when verse two begins:

Mother of Muses sing for my heart

– it would not be unreasonable to assume that the song has a double-refrain structure, and that the last line will be a repetition of the first. That is almost what happens, but not quite. The last line goes:

Mother of Muses sing for me

– in other words, the refrain from the first verse. So is that the real refrain?

As it turns out: no. In verse three, the muses’ mother isn’t mentioned at all, in verse four, she shows up in the penultimate line (“Mother of Muses, wherever you are / I’ve already outlived my life by far”); verse five begins once more with “Mother of Muses”, and for the remainder of the song, she is absent.

Is this a refrain at all? A refrain has two functions: to maintain a certain topic or theme throughout the song, and to establish a structure, both narratively and formally. What Dylan does in “Mother of Muses” is to separate the two functions. He discards the structural function that a regularly recurring refrain fulfills, but the many repetitions of the title phrase – always in places where we are used to expecting a refrain – may trick us into perceiving a regular refrain, as well as keeping our focus on the main theme, no matter how irregularly it actually shows up.

REFRAIN ON STEREOIDS. “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” is the most exuberant refrain song on the album, with many different kinds of refrains in the air at the same time.

All the regular verses end by the book, with refrains of the punchline type:

Down in the [variable, most often “down in the flatlands” or “down on the bottom”, but others occur too], way down in Key West

Scattered irregularly through the song – four times in total – there is also a full-stanza refrain. The first of these goes:

[r1] Key West is the place to be

If you’re looking for immortality.

Stay on the road, follow the highway sign.Key West is fine and fair;

If you lost your mind, you’ll find it there.

Key West is on the horizon line.

– and the second:

[r2] Key West is the place to go,

Down by the Gulf of Mexico,

Beyond the sea, beyond the shifting sands.Key West is the gateway key

To innocence and purity.

Key West, Key West is the enchanted land.

This might indicate a structure where the stanza refrain begins “Key West is the place to …” with different continuations, whereupon the second half of the stanza begins by repeating the “Key West” motto and ends with yet another observation about what Key West is.

That is not entirely true. The last two refrains begin and end with “Key West is …”, but only the last continues “… the place to …”. In the third refrain, these are the only lines that use the motto (the last line echoes the double motto in the last line from refrain two):

[r3] Key West is under the sun

Under the radar, under the gun

You stay to the left, and then you lean to the rightFeel the sunlight on your skin

And the healing virtues of the wind

Key West, Key West is the land of light

– whereas in the fourth and last it is hammered in in four out of six lines:

Key West is the place to be

If you’re looking for immortality

Key West is paradise divineKey West is fine and fair

If you lost your mind, you’ll find it there

Key West is on the horizon line.

We see something of the same separation of the refrain’s formal and thematic functions as we saw in “Mother of Muses”, but on stereoids: not only is Dylan using many different refrain types at the same time, from simple word repetitions to full stanzas, but he is also toying with the line between refrain and mere repetition: when is something “just” a repetition and when is it an actual refrain? Since the function of the refrain is already in play, it is difficult, if not impossible, to draw that line, and that seems to be the point.

REFRAIN ON PROZAC. Last but not least: “Murder Most Foul”. Upon first hearing, the seventeen-minute song seems like an endless series of rhymed pairs of lines, with no clear structure. But four times during these seventeen minutes, the words “Murder most foul” are sung, followed by a brief instrumental interlude. The interlude is heard one more time, so in total there is a hint of a large-scale structure where the song consists of four or five sections.

To call these four occurrences of the song title a “refrain” may be to stretch the terminology. And yet – if we stick to the two criteria of thematic constancy and formal structuring, they actually check both boxes, albeit it requires a wider attention span than usual in refrains.

Great Verses

This irregular sectioning of “Murder Most Foul” is one of the most characteristic features of the album as a whole, and where the heritage from “Cross the Green Mountain” shows most clearly. Each of the five sections – I will call them Great Verses – consists of an irregular number of ordinary verses. In the case of “Murder Most Foul” even these “Small Verses” vary in length. The first looks like this:

First a slow, monotonous oscillation between C and F while Dylan recites on a single tone.

Then, as an underplayed “climax”, the chord shifts from F to G and Dylan’s voice rises one tone to D. The Small Verse ends with a return to F, in preparation for the beginning of the next verse.

Each Great Verse consists of a varying number of such Small Verses: 3, 5, 5, 2, and 6, to be precise, where the last Small Verse in each Great Verse ends with “Murder most foul”.

The same kind of irregular subdivision in Great Verses is used in several of the other songs on the album. Most extreme (in addition to “Murder Most Foul”) is “My Own Version of You”, with the distribution 1-1-2-2-2-1-1-5:

“I Contain Multitudes” and “I’ve Made up My Mind to Give Myself to You” both have a gradually diminishing number of small verses per Great Verse (3-2-1 and 2-2-1-1, respectively), whereas “Key West” gets a gradually longer distance between the refrains (2-2-3-3).

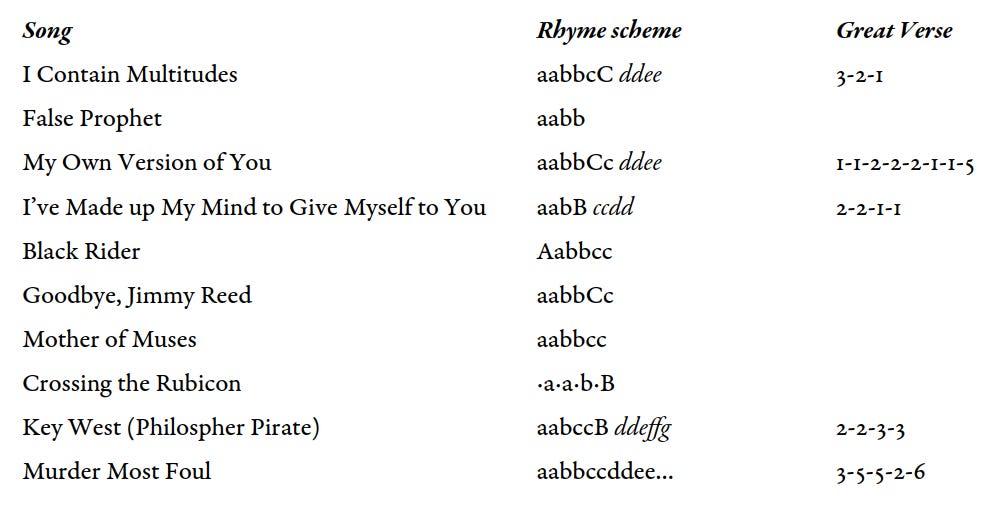

All this gives the following table, outlining the Rhyme schemes and the Great Verse structures of the album as a whole. In the rhyme schemes, I have indicated line-refrains with capital letters, and additional stanza refrains in italics:

Seeing the complete picture like this, especially the refrain column, gives rise to a couple of final observations. Most of the songs use a pattern with three pairs of rhymes (aabbcc), in some cases two pairs (aabb) – this goes for the two blues songs False Prophet and Crossing the Rubicon as well as most of the stanza refrains. The one song that stands out is Key West with its aabccd pattern both in the regular verses and in the stanza refrains.

The minimalist element on the formal level, then, can be summed up: there is a narrow range of means – virtually unchanging rhyme patterns, long chains of verses – and repetition that is always slightly irregular, which breaks the potential monotony and creates exactly enough variation to retain interest despite the long, repetitive songs.

In the next issue, I will take a look at the area where the minimalism of Rough and Rowdy Ways is most pronounced: the melodic level.