The Minimalism of Rough and Rowdy Ways III: The Variations (Dylanology 32)

In the third and last issue in the series, I focus on Dylan's new approach to phrasing, and the whole series is summed up

When I’ve called Dylan’s work on Rough and Rowdy Ways some kind of minimalism, it is not only because of the reduced means of expression. Minimalism as a musical form or direction – exemplified by the work of the American composers Philip Glass, Steve Reich, and Terry Riley – is not only about reduction and repetition, but just as much about the small variations that take place over the constant background formed by the minimalizing.

In the case of Rough and Rowdy Ways, these variations occur on virtually all parametres – from the album as a whole, down to the minute details in every single phrase.

The broad range of refrain types, formal schemes, and rhyme patterns, as I discussed in the first post, can be regarded as one such form of variation, on the highest level.

The same goes for the different ways the lines of text are distributed over the musical forms. In the previous post I mentioned how the harmonic pulse briefly increases in the refrains of Key West, so that they fill eight bars instead of the twelve bars of the verses.

I Crossed the Rubicon has the opposite distribution: the first four lines are rushed through in four bars, while the last four lines are stretched out over eight bars.

The Secret Sauce 1.0: Phrasing

But if there is one area where the wealth of variation has always been central to Dylan, it is in his phrasing. Where he really shines as a singer is in his ability to sing monotonously over anything whatsoever, with such conviction and power of persuasion that one gets swept along also when one knows, rationally, that it is monotonous, repetitive, unpretty, inelegant, unaesthetic.

It’s Alright Ma is one example from the early days; Highlands comes to mind from a later age, and as I discussed in the previous issue, the entire Rough and Rowdy Ways album is a showcase in expressive monotony.

But there is nothing magical about this. The musical area where it above all happens, is the one of the musical parametres that I left out or evened out in the reduction of Key West: the rhythmical level.

When I say “rhythmical” I don’t primarily think of the purely musical aspects of rhythm, such as metre and syncopations, but the textual: accents and emphases, and their importance for phrasing.

At a general level, one of the most interesting observations that can be drawn from the kind of close study of Dylan’s singing that I’ve been doing in Dylanology, is how closely he is able to approximate his singing to spoken language, while still clearly singing. This mix has always been at the centre of Dylan’s expertise.

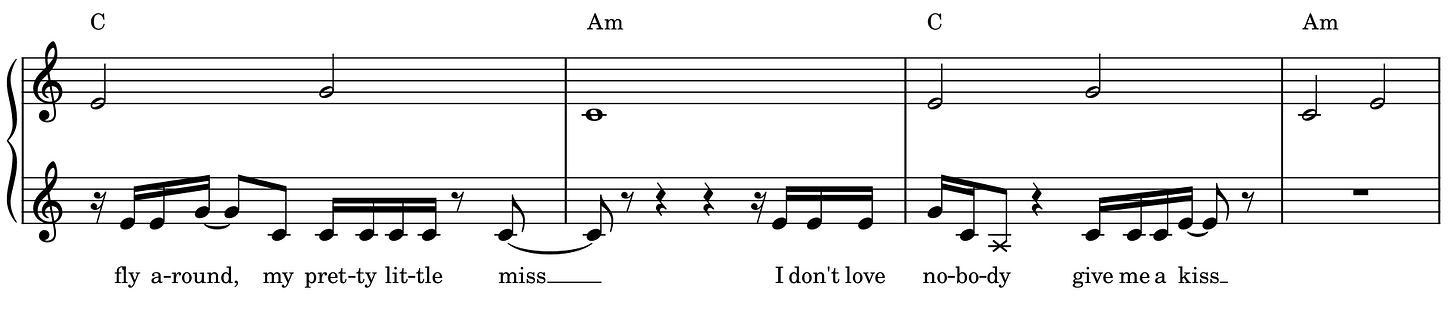

Take the following passage towards the end of Key West as an example:

If we remove all pitches and just read the words, with the rhythm from Dylan’s singing, we end up with something quite close to a representation of spoken language:

The pitches add yet another layer of potential meaning: the high notes on “(a)round” and “no(body)” correspond with the natural accents of the text. These two syllables are nuanced musically in two different ways: the first is syncopated – the accented syllable “…round” falls on an unaccented beat – which gives it a hint of instability; the second falls squarely on the first beat of the bar, thus giving the word “nobody” an extra emphasis.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dylanology to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.