Why Dylan Should Not Have Received the Nobel Prize (Dylanology 26)

The first of three texts about Dylan as a literary figure, about reasons for being right or wrong, and about prose music

One sunny spring day in 1997 I was sitting at a café discussing today’s great news item with a friend over a cup of strong coffee and a gigantic cinnamon roll: someone had nominated Bob Dylan for the Nobel Prize in literature.

The news was mostly received as a slightly amusing provocation.

Later that year, the Laureate of 1997 was revealed. The prize was awarded the Italian playwright and actor Dario Fo. Fo’s work depends to a large degree on improvisation and non-literary forms of expression, with inspiration from mediaeval theatrical traditions such as the commedia dell’arte.

My friend and I agreed that while Dylan’s candidature was highly unlikely to begin with, with Fo having received the prize it was completely out of the question with a Nobel for Dylan, no matter what ideas the Nobel Committee may have about his literary merits: they would never give the prize to phenomena like Dylan and Fo – both safely placed in the very outskirts of the world of literature – twice in Dylan’s lifetime. And even at that time, he was already no longer a young man.

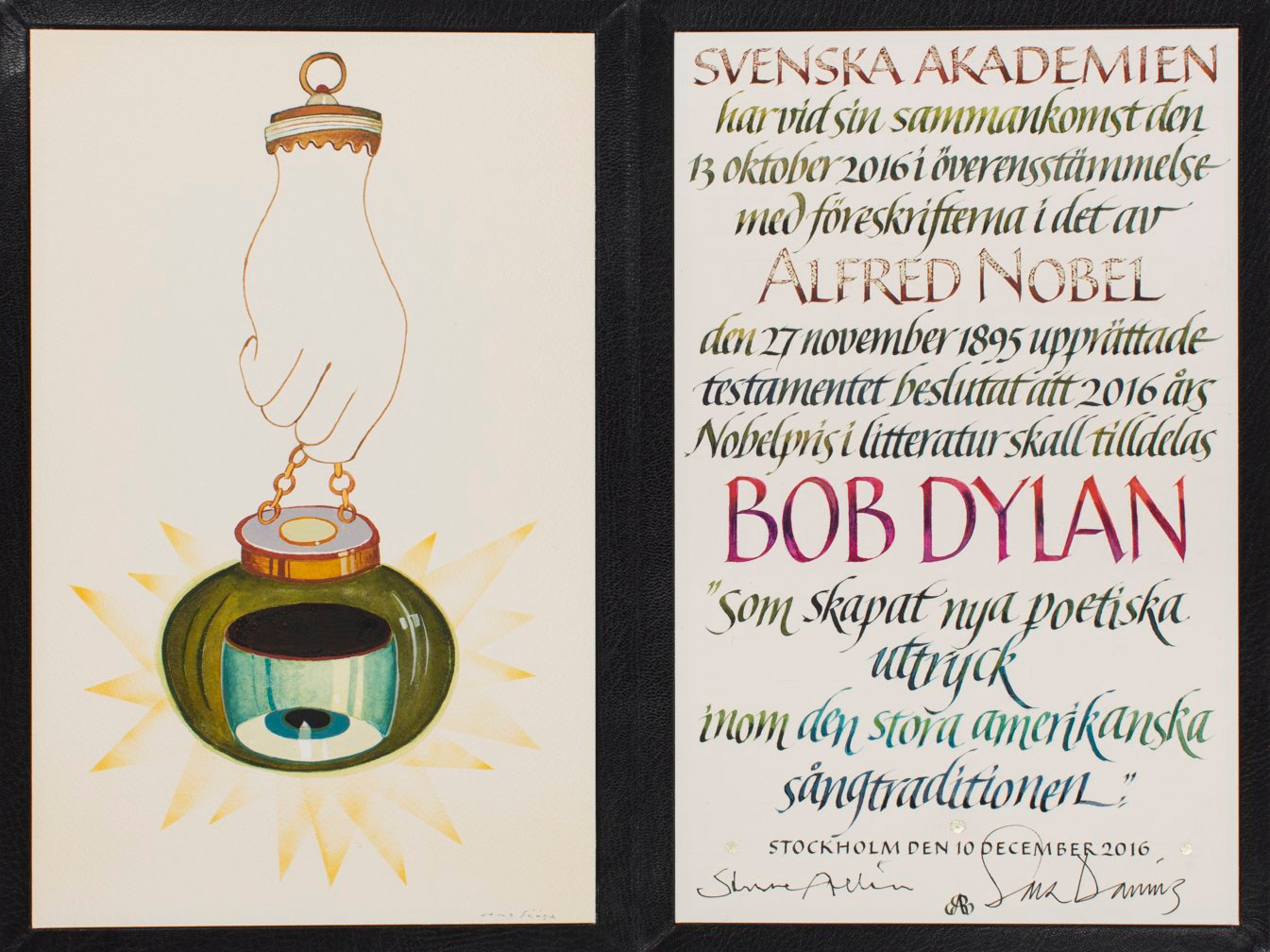

It was therefore eerily portentous when on 13 October 2016, two things happened. Early in the morning it was announced that Dario Fo had died. And at 1 PM, it was announced that this years winner was Bob Dylan.

So we were right, my friend and I: there was not room for two Laureates of their kind at the same time.

“Are you happy?”

“Are you happy?”, people used to ask me when Dylan got the Nobel Prize. Or: “What do you think – was it a correct decision?”

To the first group of questions, I could only answer: “I didn’t get the prize, so why should I be happy?” And to the second I would have to answer, as I maintained already in 1997: no, it was a bad decision.

Let it be said already at the outset: when I object to the prize, it is not because I don’t value Dylan’s literary qualities. A much longer line of argument is involved, and in the following, I will go through that line, because it goes straight to the core of what Dylan’s form of art actually is.

The TL;DR

The “Too Long; Didn’t Read” goes: giving Dylan the Nobel Prize of Literature is an error of categories: Dylan can not be awarded a Literature prize, because what he is doing is not literature. He is a singer: he writes songs and sings them, and even though those songs partly consist of texts, and those texts are of an outstandingly high level, and for many are what define their image of Dylan, all of this is not enough to call him a “literature guy”. Dylan’s art form is precisely song, as an arena for an intricate play with the boundaries between language and music, and between the poetic and the prosaic. What makes Dylan unique is his particular way of positioning himself in this matrix.

The Nobel Prize may be meant as a well deserved honour, but it also cements an image of Dylan’s art which stands in the way of a clearer understanding of his art and of why it is that Dylan – against all odds – has achieved the position he has. The Nobel Prize makes it more unclear what it is that Dylan is doing, including what part the lyrics are playing in this regard.

Giving him a literature prize, in other words, is to underestimate him, not to honour him.

That’s why it was a bad decision.

The Bad Arguments

I will return to the core of this argument, but first we have to do away with the really bad arguments against Dylan’s Nobel Prize.

The “Wiggle Wiggle” argument: Dylan has written some really lousy poetry, not worthy of a Laureate

This may be the most common argument whenever doubts are aired among Dylan aficionados. Outside of these circles, hardly anyone knows “Wiggle Wiggle” from Under the Red Sky (1990), but it is frequently mentioned as Dylan’s worst song.

The word “wiggle” appears 55 times in total, in poetic turns such as this:

Wiggle, wiggle, wiggle like a gypsy queen,

Wiggle, wiggle, wiggle all dressed in green,

Wiggle, wiggle, wiggle ’til the moon is blue,

Wiggle ’til the moon sees you.Wiggle, wiggle, wiggle in your boots and shoes,

Wiggle, wiggle, wiggle, you got nothing to lose,

Wiggle, wiggle, wiggle, like a swarm of bees,

Wiggle on your hands and knees.Wiggle to the front, wiggle to the rear,

Wiggle ’til you wiggle right out of here,

Wiggle ’til it opens, wiggle ’til it shuts,

Wiggle ’til it bites, wiggle ’til it cuts.Wiggle, wiggle, wiggle like a bowl of soup,

Wiggle, wiggle, wiggle like a rolling hoop,

Wiggle, wiggle, wiggle like a ton of lead,

Wiggle – you can raise the dead.Wiggle ’til you’re high, wiggle ’til you’re higher,

Wiggle ’til you vomit fire,

Wiggle ’til it whispers, wiggle ’til it hums,

Wiggle ’til it answers, wiggle ’til it comes.Wiggle, wiggle, wiggle like satin and silk,

Wiggle, wiggle, wiggle like pail of milk,

Wiggle, wiggle, wiggle, rattle and shake,

Wiggle like a big fat snake.

The argument goes: a so-called poet who can sink to the level of “Wiggle Wiggle”, does not deserve the prize for “World’s Best Author”.

And there may be something to that – can this in any way be compared with Hesse, Hamsun or Hemingway?

Perhaps not. But there are flaws in this argument – at least three. If Dylan had only written texts like “Wiggle Wiggle”, he would never have been considered in the first place, so the question should rather go: must every line a Laureate writes be of world class, or is there room for weeds among the laurels?

The genre criteria also play a part in muddying the waters. A three-minute song, possibly thrown quickly together to fill an album side, cannot necessarily be judged by the same criteria as a 400 page novel. Was every newspaper article Hemingway wrote pure gold? Hardly. Would García Márquez have rushed a sub-par novel just to get it out before the Christmas sales? Probably not.

But where the “Wiggle Wiggle” question actually becomes interesting is when one tries to ask: is it really that bad?

It is easy to ridicule all those “wiggle”s, but the lyrics are actually worth a closer look (as Tony Attwood at Understanding Dylan has also done).

First the wiggles themselves: they are all about things that are wiggling, jiggling, twisting, turning, quivering, quite often with a death twist or a sex twist or both. Add to this that the whole album is deeply influenced by nursery rhyme, and that Dylan was a new dad again at the time, and the seemingly silly wiggles turn into an intriguing, exciting – and slightly disturbing and macabre – cocktail of the Garden of Eden, vampire saga, a bar crawl in the red-light district, and lunar mysticism.

Dylan brews this mix in the same kind of cauldron that I discussed in my analysis of “Gates of Eden”: by establishing clusters of metaphors around strong and open images.

Death is one – of course! “Wiggle, you can raise the dead”, one of the verses ends, and with that key in hand, the last line “Wiggle like a big fat snake” gets drawn into the life-and-death circles. And what is a wiggling rolling hoop if not a symbol of death, the final moments before the forward movement stops and the hoop collapses and dies to the ground, wiggling ’til it opens and wiggling ’til it shuts.

There is also a lunacy thread: the blue moon, of course, but also the green-clad gypsy queen, wiggling her way through the crowd (to the front, to the rear), sounds like a shamanistic, ecstatic seance once that particular stage has been set.

Then there’s the outcast who ain’t got nothing and got nothing to lose, crawling right out of here on his hands and knees, wiggling his way through a swarm of bees buzzing and biting and cutting and coming down on the poor fellow like a ton of lead, ’til he vomits fire:

Wiggle, wiggle, wiggle, you got nothing to lose,

Wiggle on your hands and knees.

Wiggle ’til you wiggle right out of here,

Wiggle, wiggle, wiggle, like a swarm of bees,

Wiggle ’til it bites, wiggle ’til it cuts.

Wiggle, wiggle, wiggle like a ton of lead,

Wiggle ’til you vomit fire

That’s not the order in which the lines are presented, of course, but the images flow conveniently into each other and into the cluster they form.

There may be more – the pail of milk, the bowl of soup, the satin and silk may be meaningful imagery or just random things that may somehow jiggle – but somehow all these sets of images lend themselves nicely to be combined.

I will not invest much of my dylanological credibility on arguing that “Wiggle Wiggle” is indeed great poetry. It is still not a song that I enjoy very much (although musically it is not bad, not bad at all). But the point I’m trying to make is that even lightly scraping the surface of a presumably silly and horrible Dylan text supports rather than opposes the Nobel Committee’s decision: even Dylan’s worst lyrics have depths beyond what one perceives at first impression.

The Kissinger Argument: Dylan Is As Much a Writer of Literature as Kissinger is a Peace-Maker

Some maintain that giving Dylan the literature prize is just as absurd as giving the peace prize to Kissinger. This view was expressed most harshly by Tim Stanley, in an article in the British The Telegraph entitled: “A world that gives Bob Dylan a Nobel Prize is a world that nominates Trump for president”. Stanley writes:

Bob Dylan has been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. Why not? If the Nobel Committees can give a peace prize to Henry Kissinger then it can give a literature prize to a man who hasn’t written any literature. […] He is a dim star strumming a guitar; they [i.e. the worthy recipients] are suns around which we orbit.

First of all: if you’re thinking: “But isn’t that exactly what you yourself also argued in the introduction to this text? That Dylan is not doing literature?”, you’re right in thinking so, but you’re also completely wrong. In fact, the second part of this text is an attempt to describe the difference between the two seemingly identical statements. The short version is that where Stanley implies: “not even literature”, my take is that what Dylan does is “not merely literature”.

To Stanley, Dylan is merely a “dim star strumming a guitar”. And his comparison with Kissinger turns this into a moral issue: giving the literature prize to Dylan is a stain on society, a disgrace on the magnitude of giving the peace prize to the cynical war-monger Kissinger. It is not only incorrect (because Dylan “hasn’t written any literature”), is is directly harmful – to society and culture at large, to the trust that there may be genuine greatness at all, a greatness that cannot be bought with money and popularity. In other words: a culture which awards Dylan the Nobel Prize of Literature is a culture where Donald Trump can become president of the USA.

Stanley is fully aware that his attitude is snobbish and elitist; he even seems proud of it. But that doesn’t make it right or righteous, despite his pathos. Take away the guitar and the melody, and there is still a corpus of literature in there that would have made any poet proud. The good thing about Dylan is that we don’t have to take anything away.

A similar take to Stanley’s is expressed by Stephen Metcalf in an article for Slate:

It may be that Dylan’s claim to posterity will be larger than Murakami’s or Roth’s (or Wilbur’s or Didion’s), but that isn’t what is at issue in awarding the highest prize in literature to a pop musician.

Again the same condescending description, where there is an implicit “mere”: “to a mere pop musician.”

Metcalf continues:

The objection here hinges in the definition of the word literature. You wouldn’t give the literary prize to an economist or a political saint. You shouldn’t give it to Bob Dylan.

My thinking goes as follows, and who knows, I’m probably wrong. But the distinctive thing about literature is that it involves reading silently to oneself. Silence and solitude are inextricably a part of reading, and reading is the exclusive vehicle for literature.

To this I can only say: Yes, Metcalf, you’re right: you are wrong.

Silent reading is not distinctive of literature per se. What you’re talking about is the modern literary cult(ure) of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. That’s where solemn solitude is the predominant mode, where the reader contemplates in splendid isolation and lets himself be elevated by the genius author, and where reading aloud is a peculiar eccentricity that Paul Auster may cultivate, but which otherwise belongs in the nursery. But postulating silence and solitude as distinctive traits of literature is also to exclude virtually all literature before the nineteenth century, and the entire corpus of theatre from real literature. Homer? Nope. Shakespeare? Too loud. Ibsen? Getting closer, but sorry, not enough solitude.

Don’t get me wrong: There are many ways of stringing together words, and I don’t at all mind being clear about how different those activities can be. But there needs to be a conscious thought behind the distinction, not just indignant defence of the ivory tower.

Dylan is too popular

Another common argument is that Dylan somehow is too popular to get the prize. This argument can take two different forms. One states that Dylan simply doesn’t need it – he is famous enough and rich enough as it is, so the money and the glory are wasted on him. It would have been better for the world if someone who wasn’t already recognized were given that recognition. Giving it to Dylan is a wasted opportunity. Others may even deserve it better.

Nate Brown expresses this view perfectly in an article in The Men’s Journal:

In a world in which literary acclaim is scant and awards few and far between, Dylan’s recognition with the greatest global prize in literature strikes me as somewhat pointless. It’s not that I think he’s unworthy, exactly; it’s just that the opportunity cost of giving Dylan the prize is too high.

This might be a noble way to dismiss Dylan’s prize. Perhaps he is right. Or rather: of course he is right. If the Nobel prize is to be treated as an economical entity where “opportunity cost” is decisive, then it is obviously ludicrous to waste the prize on Dylan.

Then again, the Nobel is not a prize where “the swift […] win the race / it goes to the worthy”. An a less noble version of a dismissal would be to imply that Dylan’s popularity somehow stands in the way of his worthiness. A Genuine Author ought to be a little bit like Kafka or the protagonist of Hamsun’s Hunger: an introverted loner, preferably hungry, ideally with a hint of tuberculosis or syphilis or both, a merciless investigator of the human condition, watched from outside or from below – not a celebrated star with a guitar.

I’m not sure if the image is flawed or just irrelevant. There is no doubt that the romantic image of the artist does play a part in the way painters and poets are viewed, although it may not be an accurate representation of many of them. Besides, one might also argue that exactly the same figure exists in the world of popular music. Take a Hank Williams, a Robert Johnson or a Jimmie Rodgers – or for that matter a Jim Morrison or Janis Joplin: the outlaws who voluntarily steps outside to watch the world from afar.

It could be argued that one of Bob Dylan’s main contributions to the cultural world is his merging of the two outsider roles: the outlaw from popular culture and the modernist artist from the aesthetic side.

When Dylan says in “Sugar Baby”:

I can see what everybody in the world is up against

the prophetic role that he places himself in is not far from that of the romantic and post-romantic artist. And when he says:

To live outside the law, you must be honest

it is the same kind of honesty that we expect from the artist who we expect to tell us who we are.

The Real Problem with Dylan’s Nobel: The Nobel Committee’s Award Statement

In the next issue, I will go into the real problem with the Nobel Prize: the Nobel Committee’s reasoning behind it.

(To be continued … )

Wiggle is about the Israeli army. It is a great poem. You just don't understand it. All dressed in green and vomit fire are key words. Looks like I never did the whole poem

[The new chord-playing approach he described is in Chronicles, Volume 1.] He may have mentioned something involving some interaction with Tom Petty, while being on tour, to give it context, from memory.