Tangled Up In Blue III: On The Road – 1975–2006 (Dylanology 20 (Dec 2022)

A eulogy to Paul Williams through the lens of Bob Dylan, the artist's, performances of Tangled up in Blue

I really thought this would be the final part of my discussion of “Tangled up in Blue”, but it turned out to be too long for one issue. Besides, in the meantime there was Christmas, and December just seemed to vanish in a haze of meat, work, and glorous, Saturnalian hedonism. so yet again I’ve broken it up: this issue covers the live realisations of the song up until 2006.I still consider this to be the December issue; the final part, with the developments from 2007 to 2018, will come later this month – I promise!

Tragedy and Persistence: A Dedication

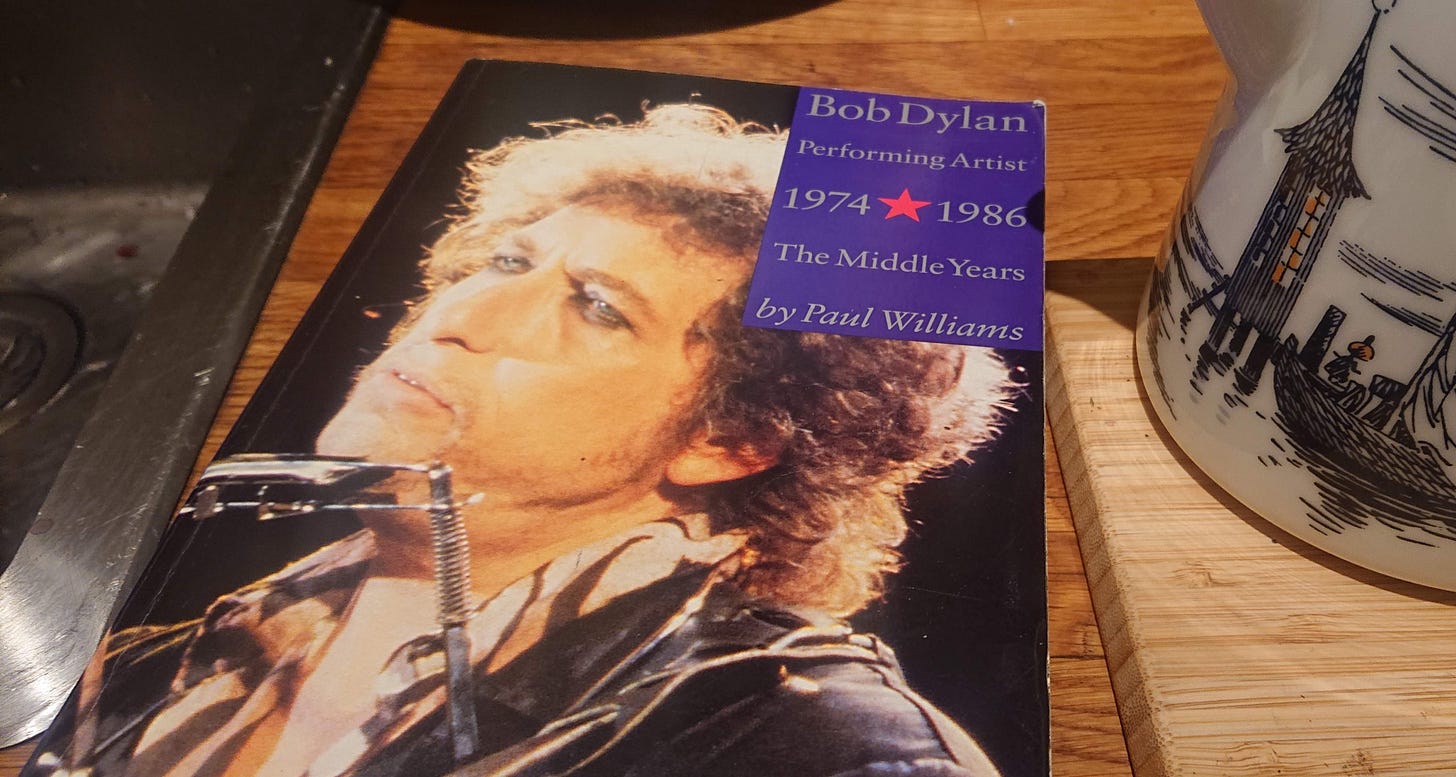

The best couple of books that have ever been written about Dylan are Paul Williams’s Performing Artist series. The title says it all: Williams regarded Dylan as a performing artist: he regarded Dylan’s live work as the ground level from which grow albums and concerts as two individual, independent but also interdependent strands, with no radical difference or hierarchy of importance between them.

His books, then, are just about the only Dylan books that take the performing aspect of Dylan’s art seriously, including the musical side of his art.

When I first read Paul Williams’s books, they were a tremendous influence, and it is not an exaggeration to say that without them, neither Dylanology nor Dylanchords would have existed. This series of posts seemed like a good place to pay tribute to Paul Williams: I hereby dedicate them to his memory and recommend everyone to read his books.

“To his memory”, because Paul Williams is also my definition of a tragic figure. When he was 17, he created Crawdaddy!, the first serious magazine of rock culture. Thirty years later, in 1995, he crashed on his bicycle, got a severe brain injury, which led to dementia and an extremely untimely death in 2013.

That’s the biographical tragedy. But there is more. Williams, as a rock journalist with a focus on the live, performed art of the artist Bob Dylan, decided to follow an entire tour. It turned out to be the 1986 tour. Now, 1986 has its moments, but I can’t help but think that of all the tours Dylan has ever done, 1986 is probably the least interesting: Dylan was – according to himself – washed-out, out of touch with his own songs. There is a certain slickness to the performances. And two years later we see the birth of the Never Ending Tour. When a serious scholar of Dylan’s live art landed on that particular tour, it is in itself a sign of tragedy.

There is a weirdly tragic element even in the layout of Williams’s book series. The first volume is called 1960–1973: The Early Years. Volume two, which culminates with the 1986 tour, is called 1974–1986: The Middle Years. After Beginning and Middle comes The End, according to Aristotle’s treatise on the tragedy, and given Dylan’s level of creativity and material at the time, one can not blame Williams for having set the stage for a vol. III that would naturally have been called 1987–1999: The Final Years, as the last 13-year chunk of the history of an artist on a steady course of slow descent into oblivion just in time for the new millennium.

As we now know, 1986 was not the beginning of the end, but the start of a complete redefinition of what a musical career is. The Never Ending Tour shattered Williams’s neat three-volume plan, perhaps even more than his bike accident did. Volume III, which came out in 2004, was called 1987–2000: Mind out of Time, and for volume IV, which was planned but never came out, the intended title was The Genius of A Performing Artist: 2003–1990 and back again – a clear concession that the neatly Aristotelian tripartite scheme had been shattered to pieces.

That’s perhaps the most tragic aspect of Paul Williams’s work: that the catharsis, the turning point of the story that he was telling, occurred at precisely the point where we, the observers, must notice that the protagonist – in this case Paul Williams – dies, thus endures a “pain that evokes pleasure” in us, the spectators, to quote Nietzsche.

“It’s All In The Riff”

Despite my general praise for Williams, I have one qualification, and that is the same objection I have against most writers about Dylan: when it comes to the musical side, Williams all too often ends up saying things like: “It’s all in the riff”. What does that even mean – “it’s all in the riff”? What is in the riff? Are we expected to simply understand what this means, by somehow connecting to the hub of emotions that is Williams’s intuitive connection with Dylan and his riff, after which we too can see “it all”? No, it’s not enough to say: “it’s all in the riff” as if that says something profound. It doesn’t. “It” is not all in the riff. You have to say: what is it about the riff? Is it the concrete notes that are being played? The pace? the attack? The phrasing? The relationship to tradition? etc. What exactly is it about the riff?

That is what is missing in most rock journalism. And that’s why I’m writing this, and everything I have written about Dylan’s music making.

With this in mind, take a look at the following chart of all the performances – live as well as studio – of “Tangled up in Blue”:

The song was written just at the beginning of Williams’s “Middle Years” volume. The entire “middle years” period 1974–86 occupies five minuscule bars (if we disregard the uncirculating rehearsals from 1977 and 1980) to the very left of the chart. The glorious Rolling Thunder Revue in 1975, which produced the iconic “white face with no visible eyes in the shadow under the brim of the hat” image, is hardly more than a blip in the chart; 1984, a highly significant year in the history of the song, is a mere 18 performances, and even the monumental 1978 tour pales in comparison with the block of years in the late 90s.

The entire history of the song as a live, developing entity lies in those years after the “middle”.

So: writing the history of the song “Tangled Up in Blue” also means detaching oneself from the recording history of the song (which ends in 1984 with the Real Live version) and instead dive into the never-ending stream of tapes and torrents and internet reports and one’s own concert memories, which constitute the bulk of its history. In that sense, the history of “Tangled up in Blue” also overlaps with the history of the Never Ending Tour itself, and as such it is the backbone of our history, the fellowship of all of us who for some reason or another feel compelled to listen to yet another concert recording – just in case it hides a priceless gem.

This also means that the history of Tangled on the Road is not primarily defined by Bob Dylan the musician, but by Bob Dylan the band leader. Much of what is to come is a celebration of guitar players, their riffs, their solo licks, their ability to give life to Dylan’s ever-changing ideas about what the song might sound like on this particular tour leg.

Before the Tour that Never Ends

This is first and foremost a story of the Never Ending Tour, but for the sake of completeness I will go quickly through the performances between the album version and the beginning of the Never Ending Tour, with brief remarks on some details of musical interest.

1975: The Rolling Thunder Version

The only difference from the album version is the addition of an extra Dominant chord towards the end of the line in the second half (at “on his”/“paid some”). It is also worth noticing that while the intro is played as an alternation G–F, in the interludes between the verses Dylan uses his “signature” G–C/g–G instead.

1978: The Grand Ballad

Ah! the glory of hearing this for the first time! The 1978 version of Tangled up in Blue is such an anomaly (and perhaps, for that reason, perfectly Dylan). It was Dylan’s tool for developing a style of singing that he never used again – a hyper-expressive lamento style that seems to have grown out of the square arrangements, like a necessary counterweight.

The arrangement first appeared during the summer, when it was sung very squarely (Los Angeles, 2 June, 1978):

In stark contrast with the autumn shows, where most of the fixed melody and virtually all of the square rhythm is gone (Charlotte, 10 Dec 1978):

The stunning development of this arrangement is most evident from the way the way the phrase “they never did like mamas home-made dress” functions (in this version, at least). In the unrestrained emotionality of the autumn version as a whole, it stands alone as a glimpse of the summer version, and the squareness – which tends to make the summer shows a tad tedious in the long run – now becomes a moment of heightened emotion – a cold, menacing emotion – instead.

Harmonically and structurally, the 1978 version is a complete anomaly. It has virtually nothing left of the original song, other than the overall structure, with a first part dominated by the tonic and the subdominant and a second part where the dominant dominates. For most of that part, the relative minor of the dominant (“Dp” in the chart below = G#m instead of B) is played, perhaps as an echo of the New York version, which also has the Dp chord, but the verse ends in plain harmonic fashion with a D-T cadence – no sign of the TUIB motif or the Subdominant’s subdominant anywhere.

1984: Dark Matter

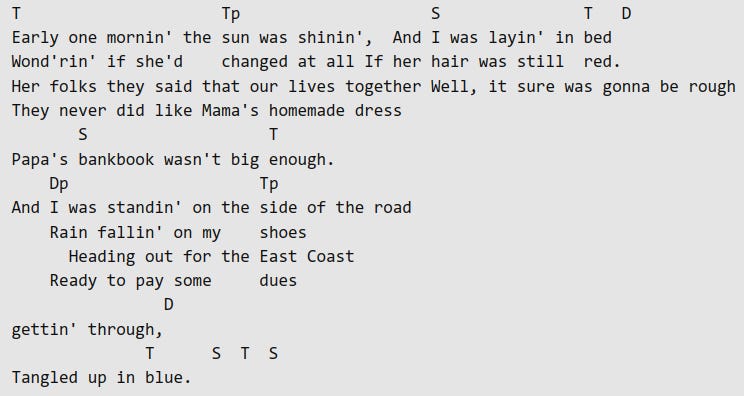

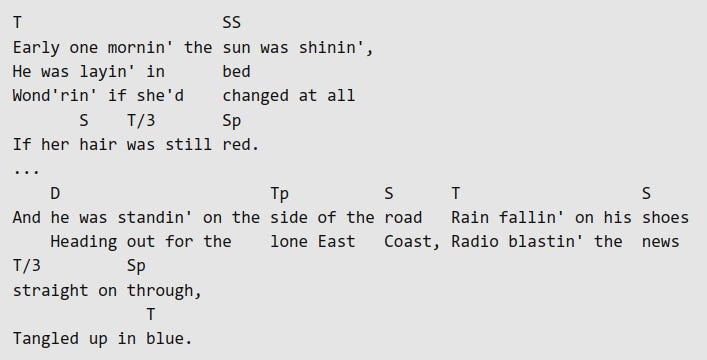

This is my most cherished version of them all, but I am not going to say much about it here, because my main concern in Dylanology is the music, whereas what makes 1984 so special is the complete rewrite of the lyrics. The new lyrics may not tell a different story. Rather, they tell the same story, but with completely different details – it’s the dark matter version of the story.

Musically speaking, it is a simplified version. As in 1975, the the interlude is replaced with Dylan’s signature move G–C/g–G. The TUIB figure is gone from the end, and both the first and the second part, which in the album version end on C and D respectively, here end with a bass-line that descends to A minor instead.

The simplifications mean that more of the dramatic potential is handed over to the vocals.

TUIB during the Never Ending Tour

There are 1725 documented performances of Tangled up in Blue. 1592 of these have been played during the Never Ending Tour.

Going through this material in its entirety would be interesting, but too daunting a task (although Dylyricus is currently doing it, in an ongoing project to log every single lyric change to the song – apparently he is half-ways through!). But I have gone through enough of it to be able to present an overview. In the following, I will survey some of the most noteworthy versions. (If you have other favourites that you think should be included in an updated survey, let me know in the comments below, or in a mail.)

Keys and Tempos during the NET

1988 – The “Ne-ver-did-a-like-a-ma-mas” version

TUIB was played a handful of times in 1987. There was nothing special about the arrangement; just energetic strumming of the album version.

The following year was the first year of the Never Ending Tour, and immediately things start to happen. Most noticeable is the exuberantly energetic singing. This was the year of the live debut of “Subterranean Homesick Blues”, and the breakneck pace of that song seems to have inspired other songs as well. This is particularly noticeable in “Tangled”, where the lyrics are rhythmicised in an exaggerated manner by inserting “a”s here and there to get straight eighth-notes, such as in the “ne-ver-di-da-like-a-ma-mas” cannonade. These “a”s should not be confused with the “a”s in early songs such as “The Times They Are A-Changin’”. There, they are corny folksiness markers; here, they are potent members of the rhythm section.

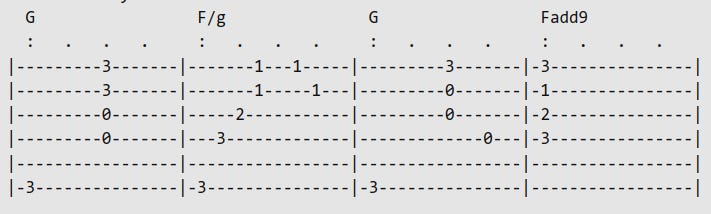

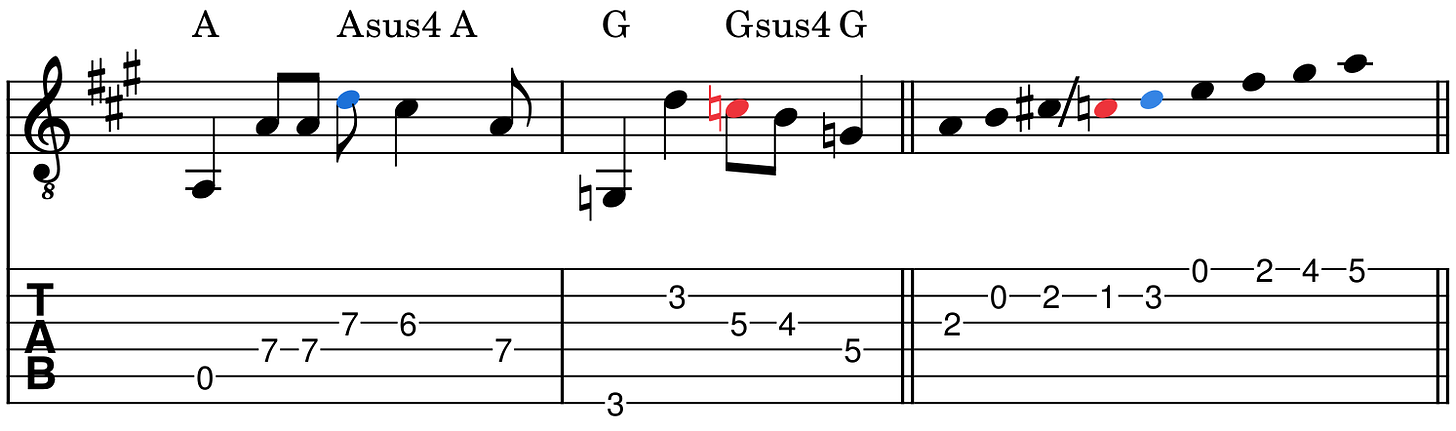

Musically, we are still mostly in the domain of the album version, but with a characteristic intro. The rhythm is energetic, to match the singing. Chordwise we are in the G family, with the characteristic addition of the tone G to the F chord, either in the bass (second measure in the chard below) or – even more characteristically – on the top string (still Berkeley, but now a couple of verses later):

1990–1995: The Electric, Breakneck Version

The 1988 version may feel brisk, but the tempo isn’t really that high – it is the energetic singing that creates that impression.

During the early years of the 90s, this changes. As can be seen from this chart, the tempo generally increases during those years, peaking in 1995 at a whopping 115.6 bpm.

I’ve grouped these years together because of certain similarities, but as can be seen from the table and the chart, there are significant differences as well.

What is common is that throughout these years, the arrangements are driven by the various intro riffs played by the electric guitar, all energetic with a strong beat. In principle, these could be played anywhere on the neck, since they don’t depend on open strings or chord shapes.

This freedom is perhaps reflected in the differences over these years. One thing is the change of guitar players, especially in 1990, although for most of the period, the position was held firmly by John Jackson, and this version might just as well have been called the Jackson version.

The most notable area of change concerns the tempos and the keys. As the chart shows, the tempo, although increasing overall, varies quite a bit. So do the keys that are used. In 1990 the song is played in E major for the last time ever (at times the arrangement is played in F, either with a capo or just by shifting the riffs around on the guitar neck), but it is also done in D major in 1992–3, until it settles on A major in 1994.

The riff-based character of the arrangement can be heard in this version, from New York, October 1990:

The B section has a slight variation from the album version: the lines end with the tonic, thus removing the subdominant altogether from that part:

In 1992, an arrangement in D major was used, with an intro that uses the open E string for a Dadd9 chord, and leaves the third finger in place on the second string throughout the riff, to make even the C an add9 chord:

In 1993, the key is still D major, but the sophisticated add9 chords and faux-fingerpicking precision-playing from ’92 are gone, replaced by driving strumming of a plain barre version of the intro riff and quick-paced licks all over the neck – faster and faster as the year proceeds. With some intricate playing, John Jackson gets to display why he deserves a place somewhere on the podium of Dylan’s best guitar players:

1994–95 bring both more of the same, and complete change. The tempo development is the same, meaning: going faster. The riff-based character of the guitar playing is still in place. And the intro reverts to the semi-fingerpicked character of the 1992 version again.

But there is substantial change as well. The song is now played in A major instead of D major. That isn’t necessarily an important change, since the riffs are played far up on the neck anyway, but there are other changes in the way the song is played, which to some extent may have to do with the key.

First, we can note that the intro is more elaborate than before. Right from the beginning, with the NY and Minnesota versions from 1974, there have been two distinct possibilities: either the intro is the same two-chord alternation as in the beginning of the verse, or some other simple chord alternation is used (e.g. the A-Asus4-A of the album version, or the G-C/g-G of the Rolling Thunder version). The 1994–5 version follows the latter alternative: The intro uses a broad, somewhat static figure, whereas the underlay for the verses is both more active with faster licks, while at the same time stepping more into the background:

But the most radical feature of this version is probably that the intro no longer consists of the two-bar alternation, but is rather a full four-bar phrase. What’s interesting is that the second and fourth chord in the chart above could be played with exactly the same tones, but because of the bass notes, the first functions as an A7sus4 and the second as a G6. Thus, schematically the intro goes |A|A|A|G|, as opposed to the album version’s |A|A|A|A| and the verse’s |A|G|A|G|.

For the verses, the riff that is used introduces a harmonic subtlety. It is played, not as a simple A chord followed by a simple G chord. The brief d in the first chord in fact turns it into an Asus4. For the G chord, the underlying chord shape of the lick is simply shifted two frets down. Thereby the place of this d, a note that does belong to the A major tone area, is taken by c, a tone that does not. Here from Prague, 1994:

As I’ve emphasised in the previous parts of this series, already the G chord introduces a contrasting tonal area, since the tone G does not belong to the A major scale. Here, that contrast is emphasised further by adding yet another, even more extraneous tone.

In this case, the added tone belongs to the third scale step, which also means that the third (c#) becomes harmonically unstable in the same way as a blues third (c/c#).

In the second part of the verse, there is a hint of the relative minor chord of the Dominant (here: C#m instead of E) the way it was played in 1994:

Whereas in 1995, the dominant is played as a true dominant (E), and it is held for half a measure longer, giving the phrase an asymmetric drive:

The Larry Arr

In 1996 Dylan returns to a simpler, acoustic arrangement again, where he himself strums the main chords. A funny detail is that he seems to be playing consistently wrong at the beginning of the second part of the verse: where there should be E - F#m - A - D, Dylan plays: E - G - A - D, while the rest of the band sticks to the “regular” chords. He does so both in Liverpool and in the Hyde Park concert. (I haven’t checked more consistently).

This peculiar detail can be observed (and heard!) here:

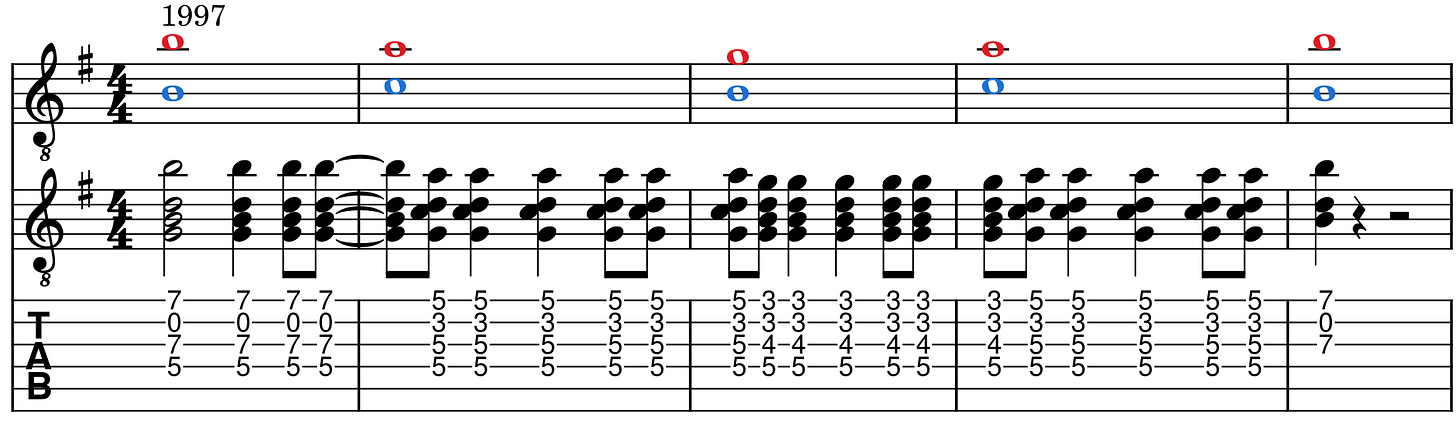

This simpler, acoustic country style arrangement was kept also when Larry Campbell entered the band, in New Foundland, 31 March 1997. In the beginning, Bucky Baxter’s mandolin was the most prominent sonic element, but some time during the US summer tour, Larry Campbell started playing a completely new arrangement of the intro. This was the arrangement that was used, more or less unchanged, for ten years, until 2007. Also, it has never been played more regularly – some of those years “Tangled up in Blue” was played more than 100 times, so it is safe to say that for many regular concert goers and tape collectors, this is the live version.

The arrangement is consistently played in A major, but with a capo on the 2nd fret, so that the chords are from the G family. There are occasional versions with the capo a fret lower, in the sounding key of Ab major.

The most prominent feature of the Larry Arr is the high, ringing b on the first string on the first note, and the melody line b–a–g–a that runs through the intro (marked in red). This b is reinforced by the b an octave lower on the open second string, which, the way it is played, produces a counter melody b–c–b–c–b (in blue).

The last bar of the intro can also go like this:

Three important things are happening here.

First, the general change from a rock/riff based song to a country/acoustic style song.

Second, the phrasing. Both the new top-line melody and the way the riff is played on the guitar cement the feeling that this is a four-bar phrase and not just a brief two-bar segment that is repeated over and over again.

Third, and most importantly, this arrangement makes the song much more harmonic, that is: belonging to a tonal harmonic musical language, as opposed to the more modal, folk idiom of the original or the blues-oriented character of the 1994/5 version.

The arrangement was remarkably stable over the whole ten-year period, although the song more or less fell out of use the minute Larry Campbell left the band in 2004.

The early 2000s is also the glory days of the abomination that goes by the name of “upsinging”: Dylan’s habit of reducing any melody – every melody – to a single tone and ending every single phrase on a leap up.

The following clip, from 2001, is a good example both of Dylan’s idiosyncratic soloing style and of how upsinging could, in the early days, be an interesting effect. The solo at ca. 3:00 is a quite pleasing example of his two-note style, and it is followed by some very interesting formulaic singing in the verse after the solo (at 3:52): gradually, the melody breaks down until all that is left is a minor third, repeated no matter what lyrics it accompanies.

The last verse (beginning at 5:24) has the upsinging version of the same thing.

And that style remained. 2002 is the same thing again: upsinging, then some more upsinging. Much more upsinging.

So much so, in fact, that when the song more or less vanishes from the setlists in 2003 and 2004, it almost comes as a relief. When I include one clip from this year, it is not so much because of the singing, but as a tribute to Freddie Koella, the guy who solos the way Dylan might have wanted to play, had he been able to. This is his solo from Toronto, 2004:

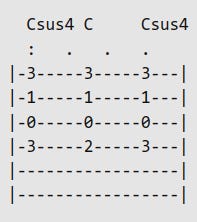

The handful of times the song was played in 2005, it was back to a much simpler arrangement, following the album version more closely, but with chords from the G family. Perhaps the strongest testament to the longevity of the Larry version is that it reappeared in 2006, but now in a

simplified version, where the four-bar phrase is once again reduced to 2 x 2 blocks.

… to be continued, with the exciting story of how “Tangled up in Blue” gradually transformed fundamentally during the late 00s and the 10s, from a Lounge Lizard, to a chromatic weirdo, a Stop-N-Go, a cool jazzer, and a remote cousin of Sweet Home Alabama.

You did not mention a particular version he used to play in april ‘99: particularly in Lubiana. So reminiscent of the ‘78 style of singing the song

Nice read, thanks! It would be interesting to know if the performance varied on the few ocasions as the setlist opener (last time Chicago 2004)?