Dylanology 21: Tangled up in Blue IV: On the Road – Again (2007–2018)

Transformations and reinventions in the 21st century

This is the last part of what ended up being a four-part series about Dylan’s best song, “Tangled up in Blue”. It covers the last twelve years (so far). As always, it is a bit long, at times it's a bit technical, and above all: it really requires that one takes one’s time to listen to the sound clips. So both I and you would much prefer if you set aside an hour, grab a pair of headphones, possibly a cozy blanket in the cozy chair, a glass of wine, one more cup of coffee, etc., and focus. You don’t have to bring your notebook – there won’t be an exam at the end of the course – but if you do make notes, feel free to write them in the comment section.

If you’re reading this as a “free subscriber”’s preview, I’d be grateful if you’d consider a full subscription. Many people have asked me if there’s a way to support dylanchords. This is the way:

The previous parts of this series are:

What’s the Deal with “Tangled Up In Blue”? – about the song itself

Tangled Up In Blue II – The First Versions – about the NY and Minnesota versions

Tangled Up In Blue III: On The Road – 1975–2006 – about the live treatment during the first 30 years

A brief recapitulation of the story so far: “Tangled up in Blue” is characterized by three things:

a specific chord (the subdominant’s subdominant or SS; i.e. the G in the A–G alternation in the beginning of the verse)

a specific structure (first section: static, centering on the tonic and the subdominant; second section: expansive, driven by the dominant; refrain: the TUIB motif, SS–S–T)

and a certain variability (is the intro an independent unit, or the same alternation as the beginning of the verse?).

These elements have been more or less stable from the beginning and through the first years of the 2000s. As I’ve shown in the previous parts of this discussion of “Tangled up in Blue” (part 1 | 2 | 3 ), there has been some variation, but not really any substantial development: it’s fundamentally the same song that has been sung during the forty years from 1974 to 2007.

The lyrics, too, have mostly been the same, with the exception of the excursion into dark matter in 1984.

The rest of the story is shorter – a mere 11 years – but more dramatic. This is how it goes.

2007–8: The Lounge Lizard

In 2007, the song is still played with G chords, but the “Larry arrangement” with the four-bar phrase is gone for good. (But as we shall see, the idea of longer phrases has not been forgotten.)

We are back to the simple two-chord alternation from 1988 again, with the pinky from the G chord remaining on the first string, to produce a high, ringing G throughout. By emphasising different strings in the F chord, different melodies are brought out and thus making these sound like different riffs, but the skeleton is the same (First: Forum, Copenhagen, 2 April, then Herning, 5 May):

Two things in particular are worth pointing out regarding this version of the song – or perhaps rather: regarding the way the song is performed at this stage in Dylan’s development.

The first is the phrasing. As I’ve mention in connection with other songs, such as e.g. “Brownsville Girl”, part of Dylan’s mastery as a vocal artist is the way he shapes his phrasing of melody lines in the broad “landscape” between musical sounds and language sounds. He sings as if he is speaking in prose, and thereby he – more than any other artist – is able to bring the meaningful elements of the sounds of speech into his music making, and conversely let the meaning potential from music influence the meaning of the lyrics.

It is as if this changes in the 2000s. The “upsinging” style is a way of disregarding the framework for creation of meaning both in music and in speech at the same time. He casts aside most of the melodic side of language (leaving only slight inflections over an otherwise static scheme), and he reduces everything to the most rudimentary formulas, he deprives himself of the available means on the musical side. Cf. the examples in the previous issue.

And it is as if this tendency is taken one step further in the 2007 shows. It is quite evident that Dylan is trying to break loose from the fixed phrase structure of the song (any song, any one of those songs that he has played 1000+ times by now). He is toying with the logical boundaries set jointly by the metrical structure of the poetic text, the musical structure of the song, and the sounds and accents of language itself.

The “Topless place” verse from Forum, Copenhagen (2 April 2007) is a good example. In the first two verses, the “melody” has mostly consisted of the octave and the fifth. Then, in the third verse it sounds almost as if he has come off on the wrong foot, and then just takes it from there; a much more scary thought is that he probably actually meant it like this.

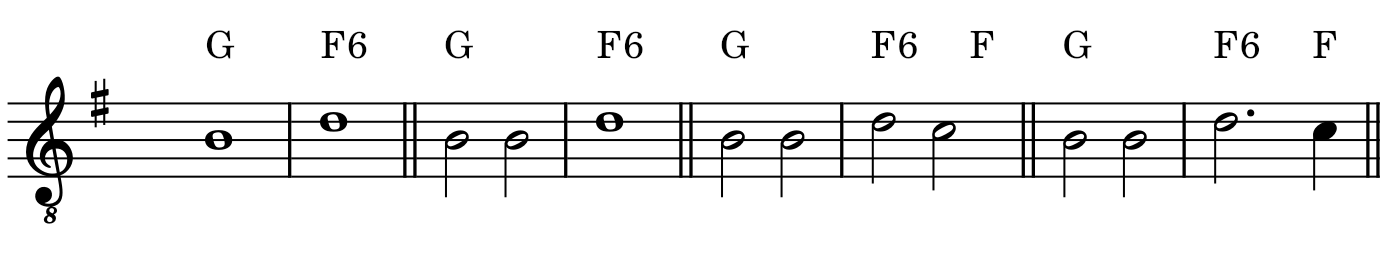

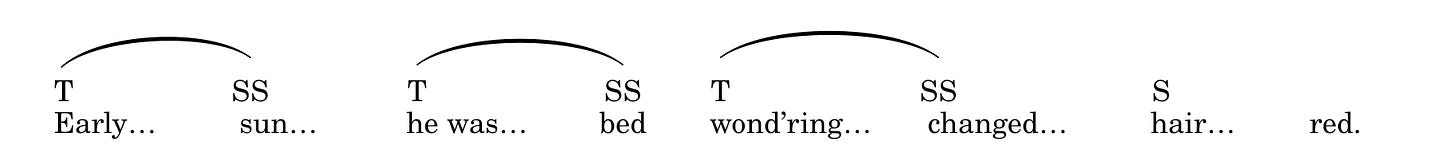

The verse is perfect as a way into Dylan’s phrasing anno 2007. Here’s an impossible exercise: in the lyrics below, tap the rhythm line (the dots at the top) with your foot a few times, just to get into the groove, then recite the lyrics as they align with the beats:

Then add the melody:

When you’re done with the exercise, compare your result with Dylan’s:

It’s an amazing feat of rhythmic equilibrism. Virtually not a single accented syllable in the text falls on the “correct” spot in the musical scheme or the poetic metre. Little wonder that it sounds as if it is falling apart at times, but somehow he lands on both feet, even though the “right beside my chair, said: ‘don’t tell me, would I know’” line is dangerously close to the edge.

This constant rhythmic displacement of actually very simple formulas seems to be a trademark of the later part of the NET.

This is not to say that he does it all the time, but it seems to be occurring with increasing frequency.

This is also not to say that it always works. In the next clip we hear the “dealing with slaves” verse from the same show. The singing at the words “she had to sell everything she owned” is one of the rare instances where Dylan breaks character, so to speak: he actually stumbles over the syllables and for once has to do what Tom Lehrer implicitly accused him of in The Folk Song Army (“It don’t matter if you put a couple extra syllables into a line”):

But my main reason for including this clip is that it contains the seed of the second of the two elements worth pointing out: the slight change in the chord sequence that occurs here, especially one little, seemingly insignificant figure that shows up in the mix. The second guitar plays the intro figure in a slightly different way, heard most clearly in the interlude after the verse, at the end of the clip.

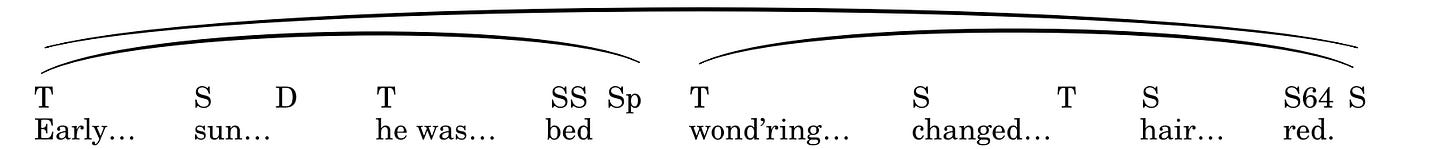

Instead of the steady alternation between G and F, with the tone G on the first string as a constant drone, the second guitar plays this:

And things are soon about to take off.

Over the summer, in the US and in Australia, this little figure gradually takes over and grows from sonic spice to being the main component in a completely new arrangement. In Atlantic City (23 June), at the start of the US summer tour, it is still the acoustic guitar that starts the song, but the F6 motif is there from the start:

and in Auckland, one month later (11 Aug), the acoustic guitar is gone altogether:

The central building block in this pattern, in addition to the F6 chord itself, is the gently rocking b-d b-d figure, in any of many possible combinations and permutations:

What really turns this into an arrangement and not just a simple chord alternation, is the way this rocking (as in: rocking chair) motion permeates the whole verse. There is a certain calm in the clear two-bar phrases – emphasised by the occasional descent through c at the end of the block (as in the last two examples above). That feeling is preserved also in the usually more expansive second part of the verse, which still has its own dominant-driven drive, and some of the melodic lines that appear in the instruments flow over from the figure above to the remainder of the verse.

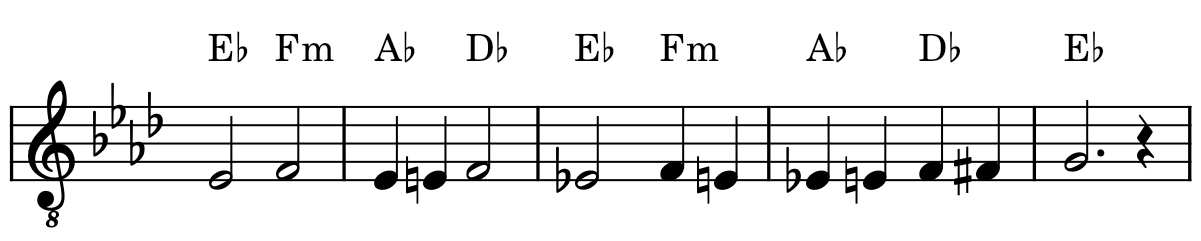

Below I have extracted the “implied melody” of the accompaniment – i.e., it is not necessarily played exactly like this, but it’s the melody that is heard in the background (based on the version from Moncton, 20 May 2008). Notice how the two versions of the dotted figure in the first part of the verse (down–down–down in red and down–down–up in blue) reappear in the second part, under completely different harmonic circumstances, thereby creating a connection between the two parts:

When I call this version the “Lounge Lizard” it’s partly because of the “loungy” calm character this arrangement has (although considering Dylan’s singing, it should probably be called the Lounge Viper instead!). But it is mostly caused by the next step in the development.

In August 2008 the transformation is complete: the dotted motif dominates the whole thing, the song is now moved to D major (with a 1st fret capo), there is now a lilting swing to it, and the second part of the verse is fully incorporated in the tonal universe of the second, through a very pronounced two-tone alternation A-B that runs through the whole section, as can be seen clearly from the extracted melody in the notes below, and heard equally clearly (Asbury Park, 13 Aug 2008):

In a sense, the whole song is turned on its head: the first part, which used to be the static section, now has a certain expansiveness to it, whereas it is the second part that is dominated by a two-note alternation.

One last detail is worth pointing out: the TUIB motif in the end is gone, replaced by a long, drawn-out suspension cadence of the most classic kind, beginning with a double suspension, which goes into a single sus4 suspension and to a plain dominant (A), before it finally lands on the keynote.

So there you have it: the development of the Lounge Lizard, from a small germ buried in a second guitar-part, to a full blown, highly characteristic and independent arrangement. This is, I think, a prime example of NET band dynamics and musical development at its best.

2009: Accepting Chaos

And what does Dylan do when something has been perfected?

He moves on. “Perfectus”, after all, means “finished” in Latin.

2009 is not a great year for “Tangled up in Blue”-lovers – in quantity, that is. It was played five times in total. But quality-wise, this is not a bad year. It features two very distinct variations.

1 – Globe Arena: Un-Tangled and Hard-Rainy

The first was played at the Globe Arena i Stockholm (23 March 2009). It begins like this:

The first thing to notice is that it sounds nothing like “Tangled up in Blue”. What it does sound like is A Hard Rain Is A-Gonna Fall:

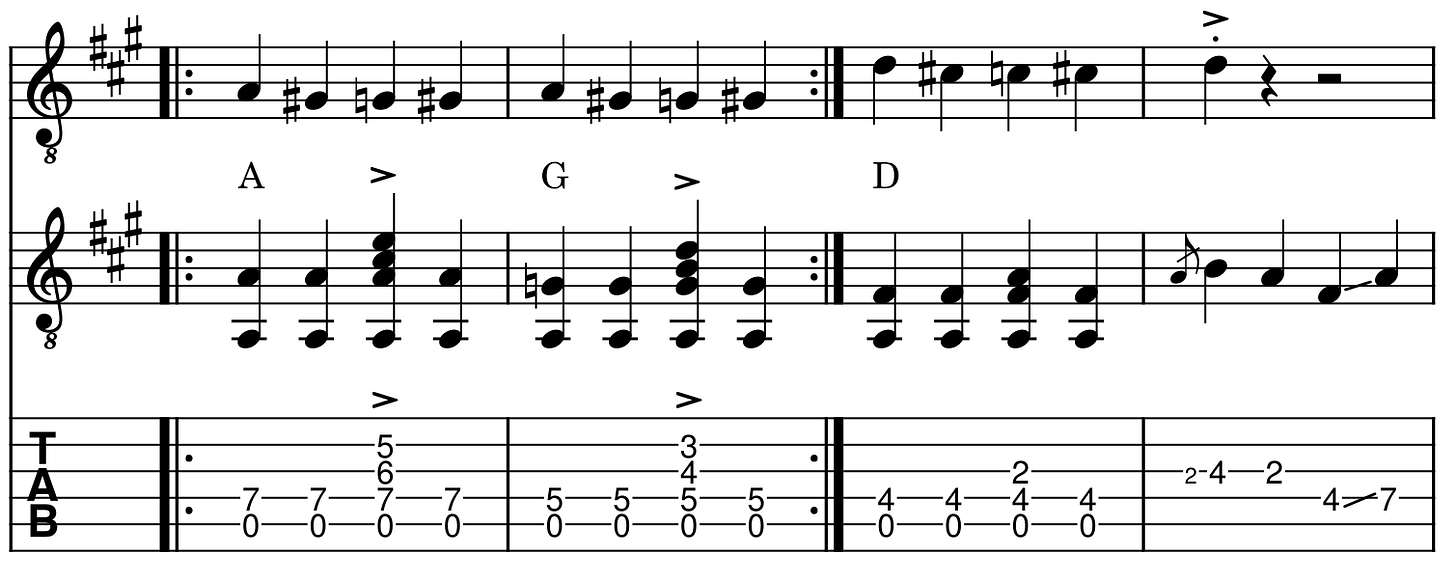

This has to do with the D chord family that is used (with a 1st fret capo, so the sounding key is E flat major). This key was used in 1992–3 as well, as mentioned in the previous issue, but then in a completely different way. Back then, the most prominent chord-specific element was the use of the open e-string as an added spice in the D chord (the third note in this tab):

Now, in 2009, it is the bass string that is exploited: the d string is sounding through the whole intro, a sustained bass tone, with chord shapes moving up and down on the neck above it – exactly like in “Hard Rain”.

And instead of a steady alternation between two chords, which is the trademark of the song from the very beginning, we now have three – perhaps a possibility that offered itself thanks to the descending figure in the Lounge Lizard.

Also, these are not just any three chords, but D, G, and A – in other words: the three chords that define the key as D major (T, S, and D). This makes this the most tonally regular of any of the “Tangled” arrangements: the place of that chord which gives the song its special “Tangled” character because it deviates from the main tone contents of the key (the SS; in this case: C major), has now been replaced with chords that emphasise the key instead.

The SS step, which is so essential to the song, is not entirely gone, though. The verses are played something like this:

There are traces of the SS in two places: in the fourth and in the eighth bar. It is clear that the tone contents of the fourth bar, both in the intro and in the verse, constitutes a C major chord, but it is not only possible but may even be preferable to regard it as something else. This is most evident in the intro:

During most of the bar, there is a C sounding, together with a g and an e. But the way it is played, the c is not really a prominent tone – it occupies the role of the middle, passing element in the descent from d to b (the red line in the examples; a close relative of the “Lounge Lizard” motif). This gives it an almost Gsus4’ish character. Thus, the tone c is still there, but its presence is strongly downplayed.

In the eighth bar, where the album versions has a plain subdominant chord, the SS chord pops up again; this time as an embellishment of that subdominant, as part of the the G–C/g–G figure. Again, this is a kind of suspension: “actually” there is only a G chord in the whole measure, but some of the tones are temporarily suspended.

This becomes even clearer if we see the fourth bar in the context of the full phrase. In the album version, there is the repeated alternation between two chords over two bars, and nothing else. Neat and tidy:

Now, in March 2009, there is a full eight-bar block, consisting of two separate phrases, and with no real repetition, although the general outline is the same:

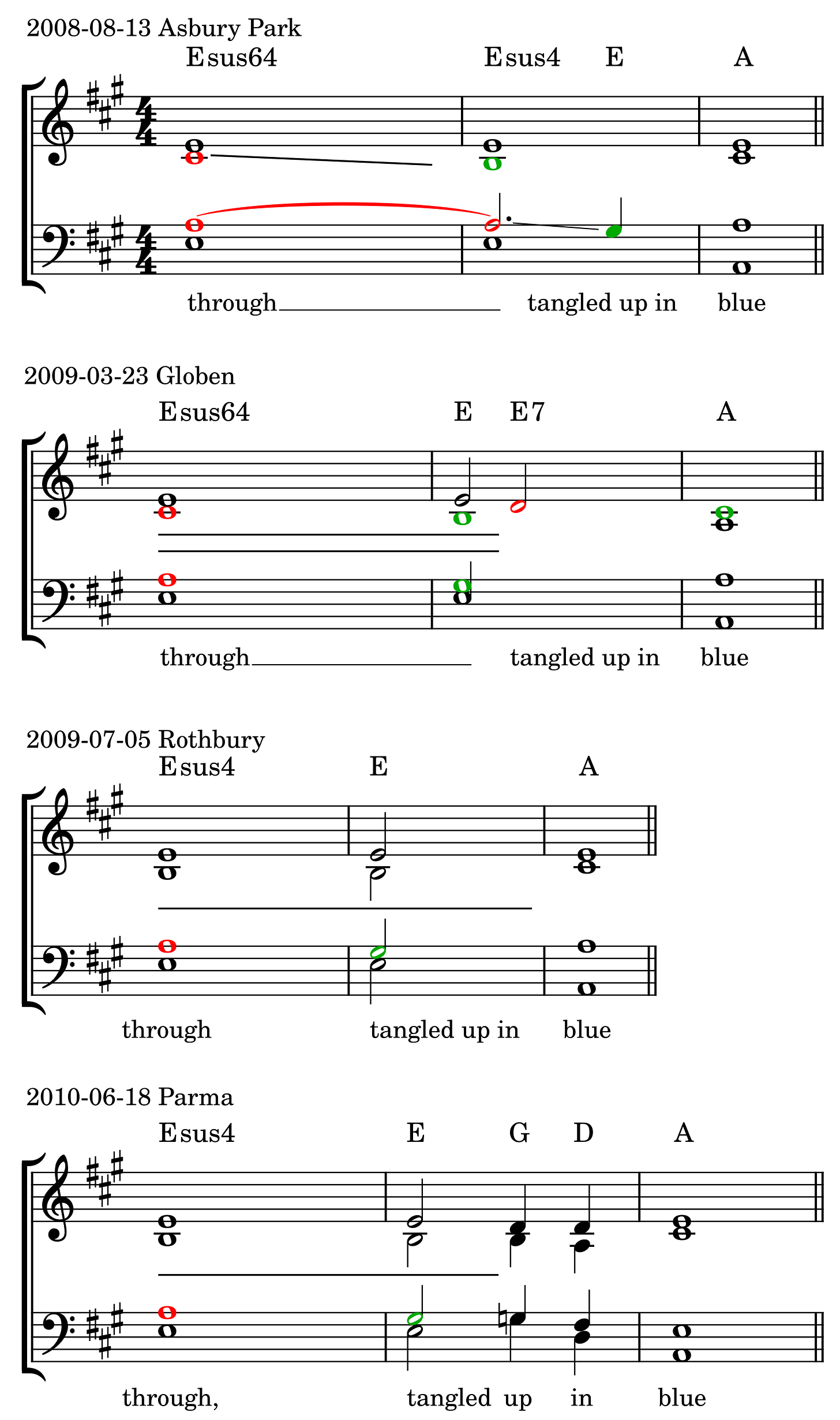

As in 2008, the TUIB motif is gone from the refrain as well. And again, it is replaced by a harmonic turn that lies as far away from the SS–S–T figure as possible: an emphasised Dominant, strengthened by being preceded by a double suspension chord (D64).

Excursus about suspensions and double suspensions: On paper it may look as if the “Getting through” line ends on a plain D chord with an A in the bass, followed by a full A chord (the dominant), and then the “real” ending on D. Why would I call this a “double suspension”?

I’m glad you asked. A suspension is a chord where one tone is temporarily “suspended”, shifted one tone up (usually) or down (as in sus2 chords), to create tension thanks to the dissonance that is the outcome. This tension will eventually be resolved, by letting the tone snap back again to where it belongs. (This is what happens in an atom when an electron is shifted to an orbit with a higher energy level; when it snaps back, the atom emits light.)

The sus4 chord is the simplest form of suspension. It resolves to a plain major chord, and since suspension equals tension and tension equals domniant, the progression usually goes on to the tonic: Esus4–E–A.

If one displaced tone creates extra tension, then surely two displaced tones must create double tension? Well, in a way, but not quite. The second example above illustrates the schizophrenic character of the double suspension. On the one hand, there is a lot more tension/release going on; on the other, the dissonance is gone. In fact, the “dissonating” chord is the same as the tonic, to which the whole passage eventually resolves.

This is the kind of suspensions that Dylan plays arund with during these years. I have assembled the cadences from four different shows, and in the music example I have indicated the dissonances (in red) and their resolutions. In the two first there are double suspensions, in the third it’s rather the rhythm that is “displaced”, and in the fourth the TUIB motif is back, with the chromatic line g#–g–f# in the penultimate measure.

2009 (2): The Chromatic Weirdo

In 2007 in the Auckland version I discussed above, at some point in the middle of the song the electric guitar plays a chromatic figure during the second part of the verse:

This doesn’t seem to have become a regular element of the Lounge Lizard, but in 2009, something similar pops up: The Chromatic Weirdo.

Its first appearance is in London, 26 April 2009. As a complete departure from 2008’s Lounge Lizard, as well as the Hard Rain version from the Globe Arena, the second completely new arrangement of the year begins with a simple riff, based on a constant pounding on the A string, and shifting chords far up on the neck:

In this form, it is innocent enough, but in London and Cardiff (24 and 26 April), Dylan doodles around on his organ in the background, and out of this comes a chromatic motif, circling around the keynote, and this is where the Weirdo is born:

In Edinburgh a few days later (3 May 2009), this figure is taken over by the second guitar in a low register, eventually echoed by other instruments and supplemented by Dylan’s voice, to create a wonderfully chaotic soundscape:

Later during the tour leg, the chord riff disappears, and all that is left is the chromatic circling and a tambourine (Rothbury 5 July 2009):

The end is cut short: there is no trace of a TUIB-figure; similar to the version from earlier in 2009, the end of the verse comes to a halt on a suspended dominant chord (Esus4) which resolves to half a bar of E, thus breaking the regular pattern, before it goes straight to the Tonic on “Blue”.

The unusually square singing, the unusually mechanical, repetitive bass figure, and the unusually weird chromatic line seems to bring out the gleeful Jokerman in Dylan, and makes this possibly the valedictorian in the Class of Strange Dylan Rewrites.

2010–17: Stop-N-Go

The first time “Tangled up in Blue” was played in 2010 was on 12 June in Linz, Austria. Does the Weirdo get another twist? Of course not – time for something new. The arrangement that is played this evening remains in the setlist for seven years, with only one semi-minor change. These are also the years when “Tangled” is a regular member of the setlist, so together with the Larry Arr’y, this is the arrangement that has been played the most times.

The arrangement is a mix of a lot of things that have gone before it.

for the intro: the sus4 figure from the album version, or something closely related, is used.

the first part has a long, 4-bar phrase instead of the repeated T–SS; but the character is static

the second part is dynamic, as usual, with a slight variation in the end

the refrain uses the long suspended figure that has been the standard for a while, but it ends with a regular TUIB motif.

What is new is above all the phrase structure: each of the original phrases are cut in two and each of the new bits gets a two-bar block of its own:

The effect is first that any sense of melody is gone. All the short blocks are recited more or less on a single tone, but with numerous micro-variations. Since the blocks don’t necessarily contain full sense units, the phrasing also does not follow any kind of speech inflection or sense-based distribution (“He star-ted-in // dea-ling with slaves”, as he sings in a later verse). As in some of the previous examples from the 2000s, Dylan has removed the potential for melodic, linguistic and metric meaningfulness, and replaced it with his very own:

Guitar stuff. I’ve chosen the version from Parma, 18 June, because it demonstrates that the main riff on the electric guitar is played without a capo, and with a barre on the 6th fret. After a few seconds, the riff is played two frets higher, presumably after someone has yelled: “Wrong key!”, and then the acoustic guitar comes in with A family chords and a capo on the third fret. In a video from Glasgow, 9 Oct 2011, Charlie Sexton can be seen playing the electric guitar part with a capo on the first fret, playing the chord with the B major family of chords, and jumping up to the tenth position to play the little lick. It feels awkward to play it like that, but it looks very natural when Charlie does it.

The effect of the stop-and-go character of the verse and the static chord sequence is that once the second part of the verse is reached, all the held-back energy is released in a single burst, and it is over before one even notices it.

2013: Sympathy for the Devil

As I said, the Stop-N-Go arrangement stays until 2017, but in 2013 a small change happens. The phrase structure is still the same, with two-bar blocks. But the main guitar riff is now:

Etc. This riff is repeated eight times, without change, all throughout the first part of the verse. The chord sequence is the same as in “Sympathy for the Devil”.

Late 2017: Sweet Home Alabama

The last incarnation of “Tangled up in Blue” so far entered the stage on 13 Oct 2017 and was a regular part of the setlist until 29 Aug 2018, which is the last time “Tangled” has been played.

It is the most radical transformation of them all. Upon first listen, it is difficult to hear anything that connects this with the original album version. But it is also a natural continuation of some of the trends that have been followed in the previous versions.

The intro is a swinging, chop-chop boogie shuffle, in which we may recognize the T–SS alternation from the original, but also the element of the 6th chords, which we met in the Lounge Lizard:

When the verse begins – using the same riff as underlay – it is clear that the broken-up phrasing from the 2010–17 Stop-N-Go version is still being used, and for a while, it sounds as if the shuffle is just another twist to the four-bar phrase:

But then things start to happen. At the point where the first part of the verse is supposed to be repeated (“Her folks they said”), the character changes completely. The chop-chop is dropped and the chords are held longer, the phrases are held together like in the original. And the accompaniment changes to F major, which could be heard as the subdominant, and at the end of each phrase there is a turn to Bb major:

This is where the second part of the verse begins – the part which is usually the dynamic part where all the action takes place, both musically and lyrically. Not this time. Instead, the chop-chop returns – this time in G minor. Other than the constant chopping, nothing happens until the very end of this section, where C (major, but with a hint of C minor) enters briefly, before the verse ends on G minor (the following clip includes the whole verse, to get the full context; the G minor passage starts at around 0:45):

This overview could be summed up in two questions: what is the form? and what is the key of this version of the song?

There is not much left of the original aabC form (where uppercase C = refrain). If we regard the chop-chop character as a distinctive feature, we now have something like an ABA form, but with regard to the harmonic progression, there are three distinct blocks, each in their own key.

And by the way: is there a common key in this song? What key is it in?

Usually, the safest way to determine the key, is to look at the end. It ends in G minor, but that doesn’t feel like a stable end point: it is reached a long time before the end, and it feels more like the preparation for the real end, than the end itself. One might say that so much effort is invested in that chord after it has been reached that it would be a waste if that should be the end.

What about C major? That’s the key the song begins with. For as long as the first section lasts, C certainly feels like the keynote. So, could the turn to C towards the end function as the keynote?

Not really. Again: that C feels like a preparation, not like a goal.

Perhaps the most satisfactory solution is to regard F major as the key. The C in the refrain would then make sense as the dominant, and the C–Bb alternation in the beginning would serve as a prolongation of that dominant. The end might then sound something like the following, where I have cheated and edited in an F major chord as the end of the passage:

With this solution, all the chords in the song would belong naturally to the main key, and the C and Bb in the beginning would be regarded as dominant and subdominant, respectively. And we could make the following comparison:

But this too is a bit far-fetched. Should the real end of the song be in the middle of the verse? And do we really hear “Sweet Home” in this passage?

There is one last complication: the end of the whole song sounds like this:

After a prolonged passage of chops in G minor, the last chord is G major.

Phew. Please – no more chords now!

In the end, it is not a big problem: it is a well established convention to end a minor piece on the corresponding major chord. But what all these interpretive possibilities do show is that the 2018 version of “Tangled up in Blue” is harmonically ambiguous.

Dylan’s Layered Creation

And that, in the end, is a perfect point to end the TUIB series on: the interpretive possibilities. What has struck me most in this marathon analysis, which has occupied me for nearly half a year now, is the constant reinterpretation that Dylan is involved in.

I’ve been aware of the fundamentally improvisational character of his singing, which I wrote about in vol. 3, about the Letterman Jokerman, and I’ve therefore been reluctant to take the review cliché about how “he always changes his songs” too seriously.

But zooming in on one song and following it through the entire Never Ending Tour has been a revelation: to see how elements change or are preserved from one slight rearrangement to the next; how, e.g., the Lounge Lizard grows out of a guitar figure in a previous arrangment; how he and the band plays around with ideas; how the “upsinging” style can actually be made to make sense, as a way of fighting the rigours – not only of the songs, but of singing itself; and how the rearrangements of the past decade and a half have involved changes in the fundamental structures of the songs, not just the surface decorations.

And it struck me: this is of course going on in every single song he is singing. Even the most dedicated concert goers or tape hunters will still only witness a fraction of this process, but Dylan and the band are standing in the middle of it, and most importantly: they are the ones who have to make the decisions and bring them to life, decide how to play the end of the verse this time, which version of the intro to choose.

In 16–18 different cases each night, once for each song, those decisions have to be made, sometimes just deciding to do the same thing as yesterday, sometimes bringing back an old song from five or fifty-five years back, and sometimes doing something completely new. Taken together, a concert then becomes a tiny piece from a gigantic web of overlapping and layering strands of constant development.

Dylanchords.com can't be visited.

From 2007 it is the years of IOT, instrument of the terror, the organ. Sometimes you didn't notice it all, but from the time you became aware it, it could ruin the concert. Suddenly PEEP! And there it was. Also in this post.